Spanish savings bank La Caixa recently brought to market a €1-billion issue of three-year cédulas territoriales at 70 basis points over similar sovereign debt. As for the investors – 49 percent of these securities backed by loans to Spanish public administrations were picked up by German or British parties and 36 percent by locals. Given the horrific recent treatment of Greek debt, this benign event probably invites a closer look at the tenets behind the classification of a nation as one of the “PIGS” – as if the mere fact that Spanish sovereign 10-years are yielding approximately the same as when the crisis broke last December, whilst the Italian equivalent pays investors 10 basis points less, were not enough to make one wonder if the British inventor of the term did not proceed from acronym to evidence and not vice versa.

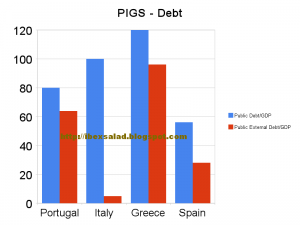

The accompanying charts might shed some light on the issue of whether all four members of this select group will end up declaring insolvency or slurping up swill from the EU trough in perpetuity because participation in the euro prevents them providing the exchange rate fix. Beginning with debt…

In Portugal, the public-debt-to-GDP ratio is comparable to France and Germany at 80 percent. That 80 percent of this is owed to foreigners invites a drastic solution in lieu of the obvious currency devaluation that is not available.

Italy is faced with, at 100 percent, a very high public-debt-to-GDP ratio. Fortunately for the Italians (and less so for the designers of acronyms who have to admit that the only reason Italy is in there is to provide an ‘I’ between the ‘P’ and the ‘G’), almost all of this money is owed domestically. This is not a currency issue.

As for Greece, the markets, now forcing the Greek government to fork over 8 percent per annum to fund itself, have decided that this country is the euro basket case. No argument here, with public-debt-to-GDP approaching 120 percent and foreign public debt the same at nearly 100 percent. Restructuring is on the cards. Expect this soon.

Spain, meanwhile, has one of the euro zone’s lowest public-debt-to-GDP ratios. Dividing this 56 percent figure by the half that is in the hands of foreigners, we find that the government owes 28 percent of GDP to outsiders. This again is one of the least onerous ratios in the euro zone.

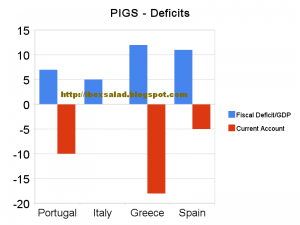

Now turning our attention to deficits…

Portugal: a reasonable (at least under the circumstances) 7-percent fiscal deficit is more than offset by its current account shortfall of 10 percent.

Italy: a 5-percent budgetary and virtually non-existent (if slightly negative) current account deficit.

Greece: a super-high fiscal deficit of 12 percent is accompanied by an astronomical 18 percent (we believe this figure is accurate) for the current account. Did we mention debt restructuring as a viable solution?

Spain: a high fiscal deficit of 10 percent sits alongside a not at all desirable current account of negative 5 percent. Not particularly reassuring, but not the worst among its peers on either count.

The chosen few

The market has assessed the Greek situation properly. The Greek position, from all points of view, is unsustainable and the end result will probably be the orderly restructuring of its government debt implied by current (and not particularly ominous given the likely outcome) 500 bps spreads over German debt. The EU will, in future, consider exactly what is to be gained from admitting new members that share no borders with other component states.

Portugal, highly indebted outside its own borders and with a large current account deficit, may be next in line for some of the same.

We will repeat ourselves. Italy was only included in this group in the first place because the British press needed an ‘I’ to make the metaphor – and did not want to use the country in the worst morass at the time, Ireland. Italy’s economic problems are purely domestic and have virtually no bearing on the proper functioning of the euro zone.

Lastly, and most relevant to Qorreo’s readers, Spain. The unacceptably high fiscal deficit of 10 percent is likely attributable to the massive rush to the underground economy (and its government unemployment insurance largesse) that accompanied the onset of the credit crisis. Something has to explain how 20-percent unemployment equates with a ‘mere’ 4-percent drop in GDP and results in a 5-percent non-performing loan ratio for the banking system. This can be expected to reverse as benefits run out, although official employment may be resumed at a lower rate of pay in many cases. This latter will affect tax revenues but will also be of value in continuing the recent improvement in the current account deficit. Public-debt-to-GDP and external-public-debt-to-GDP are not, and have never been, worthy of consideration in this context. Spain’s position in these matters shames almost all other EMU states.

We’ll leave the reader to decide if the ‘S’ belongs at the end of the ‘PG’ which remains.

________________________________________________________

Charles Butler is the publisher of Ibex Salad.

Wonderful article.

Totally agree on Italy. The British press almost purposefuly seems to prefer to ignore the fact that Italy is a successful exporting nation, with a home-grown (not problem-free) industry, closer in many ways to Germany than to the UK's wind-bag economy. This is a serious country albeit with clownish infantile politics – and a Mafia problem. The real question for Spain is: can it evolve politically and socially in a way that allows to develop the high-value-added and diversified exporting economy the Germans (and the Italians have). Or will it continue relying on tourism, agriculture and construction to the extent it has done in the past? If the latter is the case, then soon the 's' will be the 's' of "peseta" once again.

Good article. PIGS is an unhelpful media invention, like BRICs, which also includes one or two countries that don't belong (eg Russia).

There's definitely some Anglo-Saxon chauvinism at work here – a sense that northern european countries can work out their problems in a reasonable, co-operative way, while the southern are suspect and can't get their act together. aside from the numbers, there is a deep-seated fear that the Greeks will just mess it up, like they always seem to.

on the other hand, political stability is vital. what separates spain is not so much its better number, but it's better political situation. if it loses that, however, it could really be in trouble.

wld recommend this recent article by Felix Salmon on the bearish views of Noriel Roubini (aka dr doom):

Of course, this being Nouriel, it goes downhill from there: if Greece is worse than Argentina, he says, then Spain is worse than Greece. Its housing bubble and bust has left the banking sector much weaker than Greece’s; its unemployment situation, especially with the under-30 crowd, is much worse than Greece’s; and the cost of any Spain bailout would be so much more enormous than the cost of a Greek bailout as to be almost unthinkable. The only thing that Spain has going for it is that it isn’t quite at the edge of the abyss yet; if it gets its political act together and implements tough fiscal and structural reforms now, it can save itself. But clearly no one saw that happening, given Spain’s political history over the past 20 years.

full article here: http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2010/04/28/…

Roubini has made some good calls over the last few quarters. I have to say that I find his general tone to be bang on. Surprising how he has turned economics into something exciting. I have assembled a collection of interviews from Roubini, Meredith Whitney, Jim Rogres and Barry Ritholtz at financialanalystwatch.com