Spain has prosecuted more bankers, imposed more restrictions on their “golden parachutes” and seems to have hit failing institutions with higher fines for misleading investors than the United States since the outset of the financial crisis.

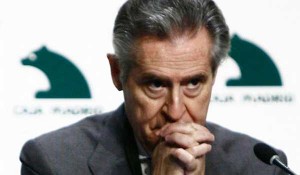

Although Miguel Blesa, the former president of Caja Madrid, which was later merged into Bankia, was released from prison without charge last week, 89 of his colleagues were awaiting sentence for alleged wrongdoing during their tenures at the helms of nine savings banks.

Meanwhile, in the United States the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has filed fewer than 50 lawsuits against officers and directors of failed institutions since 2010 and none of them has either gone to jail or been criminally prosecuted. America is seven times more populated than Spain and its financial sector represents a larger chunk of its GDP.

Eric H. Holder Jr., US attorney general, brought to light in March one of the reasons for the administration’s relative leniency with leading bankers. According to him, “the size of some of these institutions is so much that it does become difficult for us to prosecute them”, because it could damage “the national” and even “the world economy”.

However, the Spanish authorities arrived exactly at the opposite conclusion: The potential damage to the overall economy of not prosecuting negligent managers exceeded those of doing so. And they brought them to justice for possibly fraudulent operations against their companies’ interests, for carrying out badly designed initial public offerings ending in failure and for receiving handsome compensations from their companies after bankrupting them.

In Spain, some bankers have already lost their so-called “golden parachutes”. This month, the Supreme Court rejected the appeal of María Dolores Amorós, former managing director the CAM savings bank, in which she claimed a dismissal package of €10 million. The bill of her company’s bailout is estimated at over €5 billion in taxpayers’ money.

Legal limits and votes

The Bank of Spain, the main regulator at the national level, is also preparing a new norm which will require supplementing bankers’ contracts with a new clause barring them from receiving part or all of their severance payments if their companies end up losing millions or asking for state help.

American bankers have fared better than their Spanish peers. The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act only restricts managers’ compensations by requiring publicly traded companies to subject their top two executives’ salaries to shareholders’ non-binding votes. Chicago Booth School of Business professor Steven Kaplan noted recently in Foreign Affairs that in 2012 over 50 percent of shareholders supported with their ballots the wages proposed by “97 per cent of the companies” which consulted them.

Misleading markets on the part of failing institutions could have also met lighter fines across the Atlantic. Countrywide, the chief issuer of subprime mortgages in the US, and its two leading executives had to return less than €65 million to harmed investors. In Spain, Bankia, NCG and Catalunya Caixa will reimburse their clients to the tune of up to €2 billion for the fraudulent sale of preferential shares and subordinated debt. Furthermore, this penalty doesn’t prevent their cadres from going to jail, just the opposite of what happened with Countrywide thanks to a pre-trial settlement with the US Stock Exchange Commission.

However, Spain’s seemingly impressive record against financial companies’ abuses couldn’t mask that the controls had been too soft until 2012 and that this recent clampdown is in part the result of pressure from the European Union. Luis María Linde, the Bank of Spain’s governor since last summer, vowed to set right its weak supervisory role and accepted the European imposition of a new regulatory framework for his institution aimed at making cosy relationships with national banks a thing of the past. Last year, international investors’ distrust in the Bank of Spain reached such depths that they forced its then-governor, Miguel Ángel Fernández Ordóñez, to a premature resignation and obliged the government to conduct a thorough audit of banks’ balance sheets by hiring private consultants instead of the national regulator’s apparently untrustworthy and evidently angry inspectors.

It is of course ironic that though while many Spaniards complain that Blesa is getting off the hook, he is to my knowledge the only banker in the entire world to spend any time at all in prison in recent years.

The case of HSBC in the US courts to which Mr Holder refers in your article means that “Too big to fail” has given rise to “Too big to jail”. Sorry if that sounds trite but it actually is true regarding US justice. BFA-Bankia suggests the same may well be true in Spain. We’ll see.