The arrest of the former head of Spain’s employers’ association should come as a shock. Sadly, it is more likely to be interpreted by the international community as yet another indication of the many deep-rooted and extensive problems that afflict this country, the most important of which is a lack of transparency in politics and business, along with a failure to implement corporate governance practices.

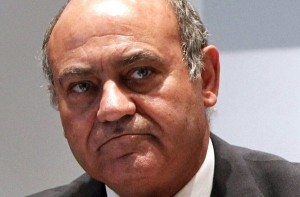

Anybody with a passing interest in the business dealings of Gerardo Díaz Ferrán will not be surprised to learn that on top of all the other charges he faces, he has now been accused of fraudulent conveyance and money laundering relating to the sale of the Viajes Marsans travel group in 2010 that he owned with the late Gonzalo Pascual.

Diaz Ferran has debts totalling €419.4 million and assets worth €5.66 million, according to the bankruptcy administrators’ report.

The latest charges come on top of those brought in June by hotel managers and tour operators against Díaz Ferrán and several associates, accusing them of concealing part of their assets in order to avoid paying judgments.

Díaz Ferrán and others at Viajes Marsans already faced several lawsuits for embezzlement. The 69-year-old was declared bankrupt in mid-2010, and all his assets have been placed under administration. He also faces charges of defrauding the Spanish tax authorities of €99 million when he bought Aerolíneas Argentinas.

Viajes Marsans collapsed with debts of €400 million in the summer of 2010. Díaz Ferran says it was his partner, Gonzalo Pascual, who died in June this year, who took the decisions and that he was not involved in the day-to-day running of the company.

Díaz Ferrán and Pascual, along with Ivan Losada of Posibilitum Business, a company specialising in buying bankrupt firms, are also accused of using money paid by customers for airline tickets on Air Comet to pay off debts within the Marsans group of companies.

Air Comet was grounded by the Spanish authorities in late 2009, leaving thousands of passengers stranded and prompting the government to step in to provide emergency transport. Hundreds of employees are still owed wages.

January 2012 saw a repeat of the Air Comet fiasco when Díaz Ferran’s Spanair low-cost carrier went bust, leaving more than 20,000 passengers stranded over the holiday period.

Díaz Ferrán rose from humble origins to prosperity, his network of tourism businesses thriving in an economy that just kept growing. From collecting the tickets as a 12-year-old on the flotilla of buses his father ran, ferrying Galicians looking for work in the capital in the hungry 1950s, during the first decade of the new century he was running an empire of 40 companies.

Díaz Ferrán and his partner Pascual, or, as they liked to be known, “G and G”, created what might best be described as a complex network of companies, which although they operated under the Marsans umbrella, were not actually part of a single holding group.

“They mixed up the accounts”

Others that have worked with the pair are less kind, describing the Marsans group as “a dog’s dinner.” One former business partner told El País that Díaz Ferrán’s model was based on his father’s bus company. “They thought that because the businesses were theirs, they could move money around as they saw fit. They mixed up the accounts, they drew money out of one company when they needed cash, and unfortunately, the younger managers lacked the courage to tell them that this was no longer a viable way to do business,” he told the paper earlier this year, adding that Díaz Ferrán also believed that his position as head of the CEOE employers’ federation would protect him.

Despite his approach to doing business, Díaz Ferrán made the right political and social connections, and in 2007 climbed his way to the top position in the CEOE, the Spanish employers’ federation.

All doors were open to him. In January 2010 amid the fallout of the Air Comet disaster, it emerged that Caja Madrid, which later went belly up and had to be rescued by the Bank of Spain, rejected as insufficient the loan guarantees offered to ensure the rollover of €26.5 million in credit outstanding to holding companies belonging to Díaz Ferrán and Pascual. Díaz Ferrán was a director of Caja Madrid.

As the top man in Spanish business, Díaz Ferrán was seen by the Socialist Party administration headed by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero as breathing fresh air into the organization after the previous 23-year mandate of José María Cuevas. He was even described as “understanding” by the main trades unions.

In July 2009, with Spain’s economy now in freefall, the government brought unions and employers together to hammer out a program to overhaul Spain’s labour market. The talks fell apart amid accusations that neither side would budge, and the government pushed through its own proposals to cut compensation and make hiring easier, which Díaz Ferrán very publically criticized, saying that they wouldn’t create jobs.

By the end of that year, Díaz Ferrán was losing support within the CEOE, for failing to leave communication lines open with the government and unions. But even after Air Comet collapsed in early 2010, he hung on, only stepping down from his post at the employers’ federation in March 2011 after Spanair collapsed.

Old-fashioned practices

Spain has been slow, compared to its EU neighbours, in implementing corporate governance. It still has many of the classic characteristics of Latin systems, such as high ownership concentration, the imposing weight of banks in the financial structure and governance of the firm, underdeveloped institutional investment and the state’s paternalistic approach to employment contracts, which leads to an excess of subsidies, low employee participation in the running of the firm, and higher unemployment than in other EU countries.

At the same time, although listed companies largely comply with recommendations for increased transparency, board independence, accountability, diversity, performance-related remuneration and, in general, more effective boards, there is still a significant percentage of companies which do not, mostly those with high ownership concentration such as those run by Díaz Ferrán and his partner in crime, Pascual.

Great piece Nick. Moving from New Zealand (the least corrupt country in the Transparency International Corruption Index) to Spain is like jumping into a freezing pool of water.