The international press has been fulsome in its praise of Pedro Almodóvar’s latest movie, The Skin I Live In (La piel que habito), with some reviewers hailing it as a masterpiece, the work of a maestro confidently taking risks, pushing the boundaries of cinema while at the same time entertaining us.

With the exception of El País’s Carlos Boyero — whose loathing for Almodóvar is long-standing — the Spanish press has been equally gushing, using that peculiarly empty and baroque language employed when the writer can’t think of anything genuinely meaningful to say, but has to fill the columns: or perhaps in this case it’s simply a way to avoid spoiling the plot.

Because that is where the problem of The Skin I Live In lies: in the plot, or more accurately, the plotting.

The film takes as its basis French novelist Thierry Jonquet’s Tarantula, a three-stranded story at the centre of which is a plastic surgeon who kidnaps a man who has raped his daughter and exacts a horrible revenge; but Almodóvar’s version soon, well, loses the plot.

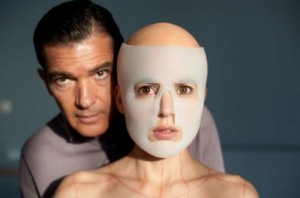

The film is mostly set in the luxurious home of eminent plastic surgeon Dr Ledgard, played by Antonio Banderas — this is the first film he has made together with the Manchegan director since 1990’s Tie Me Up Tie Me Down. A mysterious young woman who wears nothing but a skin-coloured body stocking is kept locked in a room and watched via a closed-circuit camera. An ageing, loyal house servant looks after things down in the kitchen.

The first 30 minutes or so of the film, with little dialogue, work well, and create a claustrophobic atmosphere. Who are these people? What is going on? Something is not right, we think.

And then the housekeeper’s criminal son turns up, wearing a tiger outfit (it’s carnival, as we are frequently reminded from television clips). He’s a bad lot: we know it; she knows it. But she still lets him in.

Anyway, the son soon sets the cat among the pigeons (I’m not going to spoil the plot), and we are off.

Unfortunately, we’re not: just when we’re ready to suspend disbelief, Almodóvar then fills the next 20 minutes with clunky expositional dialogue of the sort found in his beloved soap operas.

Along with a couple of red herring plot lines, we then go back six years to the start of the whole affair, moving forward in time to the present, and then on to the denouement.

One can only speculate as to why Almodóvar decided to tell the story in this way. It may be that he realised that the story he has decided to tell would be even more leaden and obvious had he not.

The problem is that even though he leaves the kidnapping of the rapist until well into the second half of the film, as soon as that happens, the answer to the presence of the mysterious young girl becomes blindingly obvious. The viewer can only sit and watch as that answer is confirmed, scene by tedious scene.

And then it ends.

Almodóvar is hailed around the world as a genius, for his unique style and approach to film making. He doesn’t follow the rules, he mixes genres, makes playful references and in-jokes, and has created a universe peopled by his re-invention of the Spaniards.

This is his first thriller. But of course it’s not really a thriller: it’s an Almodóvar film, like all the others: which means soap-opera acting, soap-opera dialogue, quirky inserts like the cameo by his brother Agustín as a cuckolded husband selling his fat wife’s clothes after she’s run off yet again, and of course, at the heart of it all, his peculiar perception of women.

A lover of women?

When I was a kid and they used to put the fashion shows on the television news, at some point Mum would invariably say: “You know, I think that fashion designers must hate women, look at the ridiculous outfits they want them to wear.”

One of the things that Almodóvar is always praised for is his insightful, sensitive, empathetic portrayal of Spanish women, but looking back over the years, I can’t help thinking of my old mum’s wise words when watching Almodóvar’s female characters traipse through their roles; essentially models whose every gesture, action, and word is dictated to the nth degree. And what’s with the comic rape, yet again?

I had hoped that having decided to make a thriller, Almodóvar would take a greater risk than usual and play by the rules, and respect some of the conventions. He could have just followed the original plot of the book. If he was going to do his own thing, then at least reinvent the genre. Instead, he has produced a clunky, unbalanced film, resorting to his usual post-modernist chicanery and smoke-and-mirrors to avoid just telling the story, side-swiping the tension that a proper thriller should have, as though embarrassed by it.

Perhaps he really doesn’t know how to make a proper film, perhaps he only knows how to make fakes.

“I had hoped that having decided to make a thriller, Almodóvar would take a greater risk than usual and play by the rules, and respect some of the conventions. He could have just followed the original plot of the book.”

I’m sorry Sir. I’m afraid you are loosing most of what being Almodovar means. He is the most famous spanish Director precisely bc’ he does not ever “play by the rules”, only his own.

You think he doesn’t show strong female characters just because they do not fit into the stereotype? I’m afraid women role in movies cannot be only black or white, neither “mujer florero” nor “Lara Croft”, there is a whole spectrum of women types and Almodovar portrays some of those. would you agree with that Sir?

And finally, “Perhaps he really doesn’t know how to make a proper film, perhaps he only knows how to make fakes”, or maybe you simply do not like his movies, like a lot of people (I dont like them all btw) which is something normal, what it does not seem normal is to question the quality of the (most likely) most awarded Dr. in a country. Perhaps he only knows how to make…his own style movies?