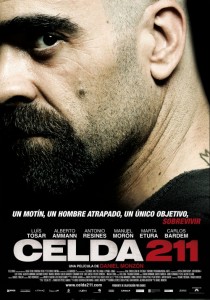

Two new films have just won the top prizes in their respective countries: Celda 211 (or Cell 211), by Spanish director Daniel Monzón; and A Prophet, directed by France’s Jacques Audiard. Both are prison dramas. Both are currently on release in Spain. Both are box office smashes. And that’s pretty much where the similarities end.

A Prophet is a confidently directed, superbly acted, universal story of a young man’s rite of passage into hell; at the same time it’s an indictment of France’s brutal prison system, where a disproportionate number of Arabs are locked away, often for relatively minor crimes.

Celda 211, on the other hand, is a lacklustre yarn based on a formulaic script, lacking in tension, poorly acted and directed, with two-dimensional characters, clunky plot twists, a few weak-kneed criticisms of the system thrown in for plot purposes, and a predictable ending that is too long in coming.

After cleaning up in cinemas throughout France, A Prophet has gone on to do good business in the UK, where it was the first foreign language film to break into the top 10 since Pedro Almodóvar’s Broken Embraces, last August. It was also a candidate for best foreign film at the Oscars, losing out to Argentina’s The Secret in their Eyes. A Prophet is already a classic.

Celda 211 was not among the three films shortlisted to represent Spain at the Oscars, and has won no international prizes, although it did well at the domestic Goya prizes.

The Americans are coming

To be fair to the film, conquest of the international market was never its makers’ intention: it’s a very Spanish product, clearly made for the home front. It illustrates an approach to fighting the growing domination of Spanish cinemas by Hollywood, a fight Spain has been losing: over the last 20 years, domestic cinema has steadily lost ground to the US film industry, which now has around 70 percent of the market. This year, around 100 Spanish films will struggle to capture an audience share of around 15 percent. That means that at least 10 percent of Spanish films made this year will not even be screened. Those that are will be given just a few days to see if they can put bums on seats. If not, they’re canned.

Morena Films produced Celda 211. Set up in the late-1990s, the company has worked hard to forge links with the US, co-producing, among others, Steven Soderbergh’s Che films and Oliver Stone’s documentary about Fidel Castro.

Morena owes its success in large part to its close links to Paramount, and to private television station Telecinco. It also regularly finds financing from state television and Canal Plus.

It’s able to attract funding largely because it makes safe, low-cost movies: aside from potboilers like Celda 211, among the more than 40 films it has produced are teen movies, documentaries, and television series. It seems to have learned from its few unsuccessful forays away from the mainstream that conventional pays off.

Celda 211 cost just under €4 million to make, and has so far grossed €12 million. A Prophet cost more than €12 million, and has grossed a similar amount, but even with the boost given by the Oscars, it is unlikely to reap its makers three times its production costs.

This approach contrasts with the reality of the nascent Spanish film industry of two decades ago, when directors such as Pedro Almodóvar exemplified the uniqueness of Spanish films, precisely by avoiding the mainstream.

“By definition, mainstream cinema avoids anything that is personal, anything that might remind us of our human nature,” Almodóvar said in a recent interview, highlighting how Spanish films have become less, well, Spanish as the country’s industry has developed.

“What is it that makes Spanish cinema ‘Spanish’? First of all, it is the absolute freedom to write, produce or direct anything you want. Secondly, we have no film industry—or what we have is very small. That means we have to make less compromises for money than big-budget films.”

But aside from US domination of their market, Spanish filmmakers also face a sharp decline in cinema attendance: around 25 percent since 2001, to last year’s 110 million tickets sold.

Looking abroad

Habits are changing: Spaniards watch more movies at home, many of them illegally downloaded; and city centre cinemas have closed, limiting outlets for adult-oriented movies.

The response by some, notably director Alejandro Amenábar, has been to make films with international appeal (such as Agora). Others, like Telecinco, which has worked with Morena, have done this (Pan’s Labyrinth, The Orphanage, and the Che Guevara films) as well as financing low-cost movies for the domestic market.

Spain’s strength since the 1960s has been to produce intimate dramas, usually with a social theme. The tradition is still alive, but it’s a genre in decline as financing dries up. Which is where a €500-million subsidy program announced by the Spanish government at the end of January comes in. Or not. It limits funding to projects of more than €600,000, which has prompted complaints from smaller filmmakers.

It’s hard to say whether the Spanish movie industry is running scared, or simply that it sees applying increasingly commercial criteria in its bid to compete with Hollywood as common sense: if so, on the strength of Celda 211, it seems to have thrown the baby out with the bathwater, and is in danger of simply replicating on the silver screen the anodyne stodge that clogs up television.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.