According to The Economist’s Buttonwood, “desperate times require desperate measures”. I am sure this is right, times in Spain are certainly getting desperate and many of the measures being implemented in Brussels, far from being radical look much more like continually closing the door after the horse has bolted.

The issue Buttonwood draws our attention to in the blog post accompanying this statement is that of migration trends within the euro area and the impact these have on trend GDP growth and structural budget deficits in the various member countries. This is an important issue indeed, since such movements seem to be an unforeseen and largely unmeasured by-product of the current monetary and fiscal policy mix being pursued by the EU and the ECB, yet the consequences they have shape the long-term future of the whole Eurozone, and with it the sustainability or otherwise of the component states.

As I said in my last Spain post:

One of the less commented features of Spain’s boom during the early years of this century is the way the arrival of economic migrants fuelled a significant part of GDP growth. The country’s population grew by more than six million (from 40 to 46 million) in the first eight years of the century, raising employment levels in both the formal and the informal economies. Migrants are still arriving, but the balance has now turned negative. According to data from the National Statistics Office, as of last June the net outflow was 20,000 a month and accelerating. That is to say a quarter of a million a year, or a million every four years. And the final numbers will almost certainly be much larger.

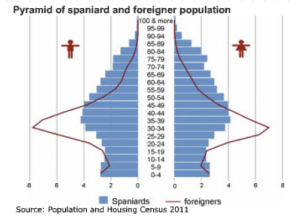

So a country which already doesn’t have enough people working to pay for its pension system now faces having less and less as time goes by, while the number of pensioners looking to claim will only grow and grow. In part that is the end result of sitting back and watching a 1.3-child-per-woman fertility rate for over 30 years. But to this grave underlying problem is now being added a new and potentially more deadly one. Those leaving are not only migrants who came earlier. Increasingly, young, educated, Spanish people are upping and leaving, and unlike in earlier periods many who go now will never return. Not only is there a massive human capital loss involved here, trend GDP growth is evidently being reduced as the workforce steadily shrinks, while all those unsellable surplus-to-requirement houses become even less sellable.

The motivation for the Buttonwood post was a research report published at the end of last week by the European Financial Economist at Jefferies International, Marchel Alexandrovich. Ostensibly his concern is about optimal currency area theory as applied to the Eurozone, but underlying this concern is a further one: that Mario Draghi and his governing council at the ECB may not be living up to their promise. That is to say they may not be doing enough to hold the Euro together. The Outright Market Transactions (OMT) policy was intended to try to remove break-up risk in the capital markets. Despite the fact that the programme has not been made operational, it has worked reasonably well in that capital flight has been brought to a halt and even reversed, the bank deposit base in most countries on the periphery is now rising, and the break-up risk component in national bond spreads has been virtually removed.

But as often happens in economic matters, solutions to one problem may inadvertently lead to another. Avoiding radical debt restructuring on the periphery, and going for a slowly-slowly correction doesn’t necessarily mean that all other things remain equal. Take the labour market, for example (I have already touched on this whole topic in my recent post on Bulgaria). As Alexandrovich points out, one of the pre-conditions for the existence of an optimal currency area is labour mobility, and the Eurozone has often been criticized on precisely these grounds. Buttonwood puts it like this:

A SINGLE market works best when its workers are mobile; Americans have shifted to the south and west over the years, for example, as jobs in the rust belt have disappeared. Europeans have the right to work anywhere in the EU and have been doing so for decades; a British series about Geordie builders in Germany (Auf Wiedersehen, Pet) appeared all the way back in 1983. But language barriers mean it is more difficult in practice for Europeans to move than for their American counterparts.

But now, suddenly, in the wake of the current crisis things are changing. While “the political process to evolve the euro area toward an optimal currency area is slow,” says Alexandrovich, “the migration data suggest that there are rapid changes made in terms of the labour mobility dimension”.

The question is, is this good news? Obviously in one sense it is, if this is needed to make the euro work it has to happen. But there is a downside, one which Alexandrovich points to: changes in the political process are lagging well behind developments in other areas, and especially in the migration one. It has been clear since the euro debt crisis that a common treasury was a necessity for the good functioning of the currency union, yet progress in this direction has been painfully slow, and full of bitter recrimination. The migration problem might be just about to bring this simmering issue right to a head.

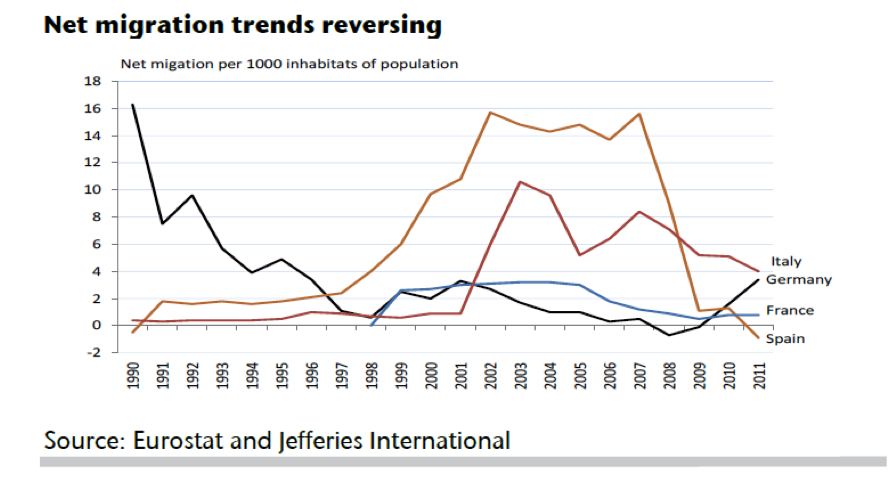

As Alexandrovich points out, migration trends have recently reversed in some key Euro states. While Spain had a rapidly growing population due to large scale immigration during the first decade of the century, migration into Germany was falling steadily, and at one point even went negative. Now all that has changed, people, on aggregate, are moving into Germany and moving out of Spain.

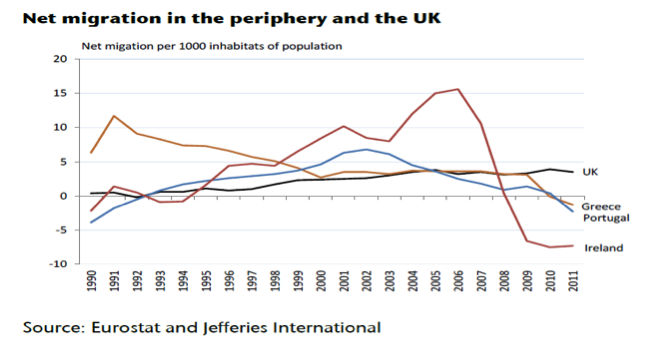

In fact a similar situation exists in Portugal, Ireland and Greece (see my last piece on Portugal), while the UK, for example, has steadily been receiving economic migrants.

These migration patterns affect working age population growth, and with this the rate of underlying potential GDP growth, the number of people paying taxes and social security contributions, the rate of new family formation and demand for new housing, etc. As Buttonwood notes, movements in population momentum are an important economic indicator, and uncertainty about where national populations are going is rising.

One of the interesting details within the latest European Commission Winter economic forecasts for instance is the downward revision to Spanish population estimates, with the country’s population now expected to shrink in size by 0.2% in both 2013 and 2014 – the previous forecast from only a few months previously was a 0.1% annual fall (see table below). This may not seem particularly significant, but these are obviously just estimates and as the economy goes through another tough year, these figures could end up worse and the decline potentially extending for several more years.

In fact, the negative movement in Spain’s population is accelerating and no one really knows how far this acceleration will go, or how long it will continue. What we do know is that the likelihood of Spain’s unemployment rate falling below 20% by 2020 is small (it is currently over 26%), and with such high unemployment the pressure to move will continue to be strong.

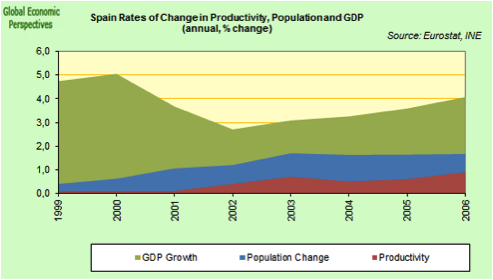

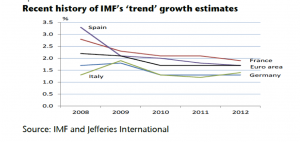

Now, if we look back over Spain’s “good” economic years, it is clear that even though growth between 1999 and 2006 was normally in the 3% to 4% range, most of this growth came from population increase, which was extraordinarily rapid, while productivity growth was miniscule, and even in the best of cases less than 1%.

Spain’s population had been virtually stationary in the second half of the 1990s, and the subsequent rise was almost entirely due to immigration, the overwhelming majority of which was of working age population, as can be seen in the chart below from the Spanish national statistics office.

Now why, if this was the case you might ask, did Spaniards feel so much better off during these years, since GDP growth per capita, and especially per working age person, was not exactly stellar. Well, the next chart tells us why.

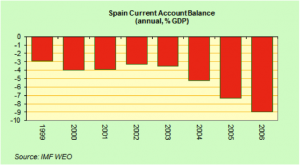

Basically, Spain as a country was getting into debt, by borrowing abroad through the European interbank market, and consuming a lot of products which were produced elsewhere. Naturally, with house prices going up each year, homeowners felt increasingly well off. Now, of course, house prices are going down each year, and exports are being increased to help pay down all the accumulated debt. So we are getting the “continually feeling worse” effect.

Not unsurprisingly, IMF growth forecasts for Spain are being steadily revised downwards to reflect the new reality. And naturally if the current working age population dynamics continue they will be revised down further and further. This is what makes listening to that continuing string of speeches from Spanish politicians just so tiresome. They continually talk about recovery being just around the corner, but in reality they have no idea what recovery will mean in Spain, or even of what they are talking about.

And there’s yet another nasty twist here. Spain’s employment legislation effectively protects older workers at the expense of younger ones. That is why while the overall unemployment rate is 26% the rate for 15-to-24-year-olds is 55%. This “older worker bias” also has implications for productivity, as a recent report by Deutsche Bank’s Gilles Moec indicates:

The dualism of the labour market in many European countries means that, on average, workers under the age of 25, since the beginning of the crisis, have contributed 4 times as much to the contraction in employment as their actual share in total employment (see Focus Europe 9 November 2012). Young workers often are the vehicle of innovation in companies and any labour market adjustment which is skewed towards young workers will ultimately reduce aggregate productivity.

Using data collected at the firm level in Belgium (which in our view is a good proxy for the Euro area in general), Lallemand and Rycx estimated the impact of a change in the age structure of staff on productivity, by adding to a canonical model of productivity based on firms’ characteristics (such as sectoral specialization and educational attainment of workforce) the share of three age groups (below 30, 30 to 49, above 50) in firms’ workforce, as explanatory variables. To provide an illustrative order of magnitude of the negative impact of the recent change in the age structure of companies on aggregate labour productivity in the peripherals, we applied the coefficients estimated by Lallemand and Rycx on the actual changes observed in Spain and Italy between 2007 and 2012 (see Figure 1). This effect is actually quite sizeable, with an adverse shock on the level of aggregate productivity of around 2% in both countries.

So really the whole current situation is most lamentable, since Spain’s ongoing loss of young talent means that the country may well be losing growth potential just as fast as the implementation of structural reforms is recovering it.

But, to go back to the start, and Buttonwood’s point that “desperate times require desperate measures,” these are just what Marchel Alexandrovich at Jefferies is calling for: serious and substantial political measures to shore up the euro fiscal system, to enable people to move without increasing instability in the health and pensions systems, and without making the difficulty of carrying through national level fiscal adjustments even worse. Spain’s pension system shortfall added at least 1% to the 2012 deficit, and the situation is only getting worse; every month less people contribute and more people retire and claim.

Alexandrovich is not, however, as Buttonwood appears to suggest, advocating “a fiscal union where tax revenue is distributed to the smaller countries to allow people to stay put”. This is what happened to the Spanish system of inter-regional solidarity and is part of the problem in Spain’s labour market. No, he is arguing for automatic health and pension fund stabilisers to be put in place, so that workers can move freely around without worrying about the implications for their parents or grandparents back home. Otherwise we really will have winners and losers coming out of this crisis, with some countries shoring themselves up, while others are (unknowingly) melting themselves down.

But first, we need to take more determined steps to really measure what is happening. At the moment our knowledge about these flows and their implications is woefully limited. As the European President of the Migration Policy Institute, Demetrios Papademetriou, put it recently: “The current knowledge base on the economic and social impacts of free movement is slim — in part because its evolving, flexible nature is difficult to capture in official data sources — but it must be improved, to afford a greater understanding of the effects on communities, local workers, and the public purse.”

In conclusion, I leave the last word to Mr Alexandrovich:

And so we have gone full circle back to the idea of an optimal currency area. The way that a banking union tries to mitigate the effects of a potential bank run, similarly one could help mitigate the effect of Spanish or Greek workers going to work in Germany by having a union where tax revenues get redistributed between the various countries. Otherwise, debt needs to be serviced by fewer taxpayers which then need to be squeezed even harder to keep the whole thing ticking over. So on various levels arguably the euro project remains incomplete and migration data simply help shine a light on some of its further shortcomings, where some countries get isolated and left even further behind.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.