Watch any film at the San Sebastian Film Festival and you can feel like you’re taking your life in your hands – two hours of it, anyway. The event, which prides itself on being a champion of the avant-garde, is a notorious game of chance when it comes to buying tickets.

So it is a bit surprising when you see a film that delivers exactly what it promises.

The Impossible (‘Lo imposible’), a US-Spanish production directed by Juan Antonio Bayona (The Orphanage) is the story of one family’s struggle for survival following the devastating tsunami that hit their hotel resort in Thailand on Boxing Day 2004.

It is based on the true-life story of Spaniards Quique Álvarez and María Belón (portrayed as a British couple by Ewan McGregor and Naomi Watts) and their three sons.

There was a certain inevitability about the release of The Impossible, the first big-budget production of its kind to deal with the 2004 calamity. Cynical as it sounds, tragedies make for good cinema, and nowadays simulating a real-life tsunami is a walk in the park for large studios and special effects teams.

What’s more, with ultra-realistic portrayals of death and mutilation frequently hitting cinema screens, shocking images are an easy resource for any director.

Happily, it is one which Bayona resists. Far from being bombarded by gory images, we glimpse occasional yet powerful scenes of the devastating physical and emotional toll that the tsunami took on so many of its survivors.

The first scenes in which we see Maria and her son Lukas (Tom Holland) fighting to stay alive and together while being washed through a torrent of sea water and hazardous debris, are deftly and tastefully directed. Bayona and the actors create a faithful and realistic portrayal of the sheer panic experienced by their characters lived, drawing a sympathy from the audience that feels natural and unforced.

There are certain elements to The Impossible that betray its status as a big studio production, not least its somewhat formulaic style. In the press conference, Bayona brushed aside criticism that he had turned an essentially Spanish story into an American blockbuster – on one hand, on a practical level. The €30 million he needed – a small amount by modern standards – were not available in Spain.

On a deeper level, however, he defended the story as essentially universal: “Spaniards were not major protagonists in the tsunami,” he said, to vigorous nodding from the real-life María Belón, who was also there.

Overall, The Impossible handles its subject in a sensitive manner and rarely resorts to the sort of mawkish triumphalism so often seen in productions of this kind. The cast offers strong yet contained performances, particularly McGregor and Watts, who get excellent support from the three child actors playing their sons.

The artist and the model

Some films are intended to tell a story, while others are pure works of cinematic art.

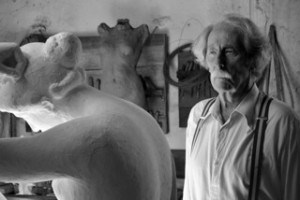

Fernando Trueba’s latest offering, El artista y la modelo, set in Nazi-occupied France and shot in French, is a film about art and, quite simply, is a work of art in motion.

Jean Rochefort plays Marc Cros, an aged artist and sculptor who, nearing the end of his life, embarks on one final work of art thanks to the arrival of a new young model (Aida Folch) recently escaped from a refugee camp in Catalonia.

There is one scene in El artist y la modelo which offers a key insight into the character of the artist and into the film itself. It is when Cros tries to explain to his model, with a passion he preserves purely for his art, the importance of a sketch by Rembrandt. How, through the smallest of details, one can sense the emotions and thoughts of the subjects of the piece.

Trueba’s characters are created with a similar attention to detail. Aside from shooting the film in stylish black and white, with an expert eye on the composition of every image, each of the characters is finely crafted. From the timeworn features of the tired old artist to the nubile, animated Mercè, the yin to his yang.

Struggling with artist’s block, Cros has almost detached himself from the human events that surround him. He is even unmoved by the naked body of his latest model. In one significant scene we see him touching Mercè almost as if she were modelling plaster, a clever reflection of an earlier scene in which he absent-mindedly places his hand on the buttock of a naked statue in order to move it.

There are other explorations of the tensions between life and death, or rather life versus lifelessness. Such as Cros’s friendship with a high-ranking Nazi and artist who reads books which are banned in Germany. Despite the shadow of philistinism, however, Cros does not fight the status quo. He is even irritated by his model’s involvement in the resistance. His only purpose is to continue with his art, a fight as worthy as any other, perhaps.

El artista y la modelo is one of the best films I have seen in the Official Section and should be a strong contender for one of this year’s awards. As is the case every year, however, the San Sebastián Film Festival will remain an open race until the end.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.