Chavela Vargas, who attained legendary status through her renditions of Mexican ranchera music throughout much of the Spanish-speaking world in her final years, died on August 3, at the age of 93.

Born Isabel Vargas Lizano in Costa Rica, before being abandoned by her parents as a child, she moved to Mexico aged 17, in 1936. Her arrival coincided with the rise of ranchera music, which like country music in the United States, was initially a celebration of rural values, but soon became a format to explore themes such as the hopelessness of love, the sorrows of which are best drowned in the bottle.

Vargas soon became part of the circle of artists and hangers on associated with painters Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, and she lived with the couple on and off during the late 1930s and early 1940s. She would perform in small bars and clubs, dressed as a man, often with a gun tucked into her belt, smoking a cigar and glugging from a bottle of tequila.

Accompanying herself on guitar, she would sing songs written by men, for men, about erotic love for women. Unsurprisingly in Roman Catholic Mexico, her open lesbianism shocked many, and undoubtedly limited her career.

Vargas’ contribution to ranchera is undisputable: she stripped the music down to its bare bones, shedding the mariachi trumpets that had come to be associated with the form by the 1950s, notably in the songs of José Alfredo Jiménez, author and singer of some of Mexico’s best known songs, such as El Rey. By performing with just a guitar, she got to the heart of her material, despite her limited vocal range, managing to imbue Jiménez’s often maudlin songs with an intimacy and authenticity matched by few. “I’ve always had the same voice,” she said in an interview. “I don’t need machines to help me sing. I sing because I sing. And I sing truthfully. Nothing interferes.”

She recorded a number of singles during the 1950s, including one of her best-known numbers, Macorina, a declaration of physical love for a Cuban prostitute, but didn’t record her first album until 1961, by which time she was a fully fledged alcoholic, with her drinking bouts alongside Jiménez among the mariachis of the Plaza Garibaldi by now having become the stuff of legend. For the next decade she continued to record, even appearing on television, and enjoyed some commercial success. In 1957 she performed at the wedding of Elizabeth Taylor to the film producer Michael Todd in Acapulco.

But by the early years of the 1970s her lifestyle had taken its toll, and following the death of Jiménez in 1973, she retired, going to live among the Huichol Indians for most of the next 20 years, fighting to overcome her alcoholism, and during which time she was largely forgotten. When this author lived in Mexico for a year in the late 1980s, doing research for a thesis on the links between ranchera and norteña music, her name never came up among musicians and musicologists.

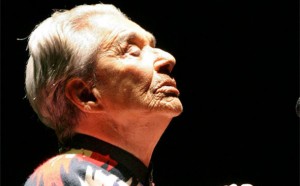

But a few years later, by the early 1990s, Vargas began appearing in small clubs in Mexico City, attracting the attention of a new generation. Her voice had changed completely in the intervening years, broken, cracked, and often unable to reach the higher notes she had once hit so effortlessly.

Almodóvar’s muse

Around this time she caught the attention of Spanish filmmaker director Pedro Almodóvar, who immediately saw her potential as a consummate deliverer of the torch song, using her material in Kika, All About My Mother, and other films, introducing her to a new audience in Spain and the United States. She resumed touring, playing Carnegie Hall, and aged 81 decided to write her autobiography Y si quieres saber de mi pasado (If You Want to Know About My Past) at age 81, in which she discussed her homosexuality. “What hurt was not being homosexual, but that they threw it in my face as if it were the plague,” she wrote.

“Nobody taught me to be like this,” she told Spanish newspaper El País in 2000. “I was born this way. Since I opened my eyes to the world, I have never slept with a man. Never. Just imagine what purity. I have nothing to be ashamed of.”

In 2002 she appeared in Frida, Julie Taymor’s film about Frida Kahlo, singing La Llorona (The Weeping Woman) with an intensity that revived speculation as to whether she had had an affair with the painter.

“I learned a lot from Frida, and I saw her suffer,” Vargas told El País. “I learned to live, and also about death.”

Last year, Vargas released a new album of Federico García Lorca’s poems and received standing ovations from a wheelchair on stage while wearing the poncho and neckerchief that had become her trademark. In interviews she said she was at “peace with life and could not ask for more,” saying that at death, she would “go with pleasure.”

Beautiful. Great article honoring a great artist.