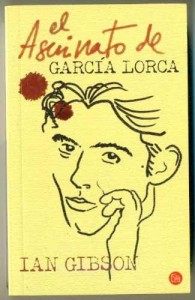

I first met Ian Gibson in 2004. While walking through the Madrid barrio of Lavapiés, I had spotted a face that I remembered from the book flap of his biography of Federico García Lorca. Like a weak-kneed groupie, I followed him into a bar and confessed I was a fan of the biography as well as his exploration of the events that led up to Lorca’s death, El asesinato de García Lorca. Gibson, who lived in the area, graciously invited me to sit down and have a drink and I spent 10 hurried minutes with him.

Seven years on, I meet Gibson at the same bar (his choice), but this time the interview has been arranged by phone and it coincides with a new edition of his Lorca biography in Spanish, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the poet’s death.

At 72, Gibson is currently working on a biography of Luis Buñuel. Following those of Lorca and Salvador Dalí, this will be the last of a trio of biographies of Spanish geniuses and the end of an era for the tireless, Dublin-born Gibson. But while Buñuel and Dalí clearly mesmerise him, Lorca has always been his driving passion, ever since visiting Spain in 1958.

“I came here because I was obsessed by Federico García Lorca – his work his poetry, his theatre, his life, the person, the people around him, the incredible things that were happening in Spain then,” he says.

Like many foreigners in Spain, Gibson has an ambivalent attitude towards the country: it both fascinates and infuriates him. Perhaps researching the lives of extraordinary characters in a country that lacks a deep tradition of biographies (“a weakness in Spanish culture,” he says) exaggerates both the fascination and the infuriation.

“There are things about Spain that I don’t particularly like, there are other things that I think are fantastic and I don’t see for the world why I shouldn’t talk about this and say what I feel,” he says. “If I have any use here it’s to say what I think about diverse issues.”

Clearly the literature and art produced by Spain, particularly around the middle of the last century, is something he admires, as is the country’s variety and its landscapes. On the other hand, he doesn’t care for the quality of political debate in Spain, or its reluctance to face up to the past.

Not everyone wants to hear such opinions, even when they are based on decades of study. Gibson has a relatively high public profile – he occasionally appears on Spanish television, wrote a regular column for El País for many years and now does so for Público. Being a foreigner who has delved into Spain’s turbulent 20th century history makes him an inevitable target for many, especially in a country that is so sensitive to what outsiders think, say and write about it.

In particular he upsets the political right. Columnist Francisco Alamán Castro holds a fairly typical Spanish-right view of the Irishman when he calls him a “tendentious historian and a cruel citizen”, for writing about “our civil war.”

“I know that the fact I’m here and I do what I do does irritate people, particularly on the right,” Gibson sighs. “There is the feeling that as the outsider: ‘who the hell are you? Why don’t you go home? And don’t, for God’s sake, criticize’.”

A false dawn

His dogged research into the circumstances surrounding Lorca’s death, near Granada, at the hands of Francoists at the start of the Civil War in 1936, is one reason Gibson manages to wind up the right so much.

In 2009, Gibson’s theory regarding where Lorca was buried, along with three other men executed with him, was the basis of a search for the bodies in the hope of exhuming them and giving them proper burials. Judge Baltasar Garzón’s order to carry out the search was a major step forward in Spain’s slow progress towards understanding its historical memory, with an overjoyed Gibson telling El País that it was “the most important day of my life.”

But the jubilation was not to last. The exact spot identified by Gibson did not hold Lorca’s body, although he believes the poet is buried somewhere nearby.

“The situation is appalling,” says Gibson, still visibly upset at the lack of official willingness to continue the search since 2009. With the conservative Popular Party now controlling Granada town hall and the local council and the Lorca family apparently unwilling to cooperate, he sees little hope of the man he sees as one of the world’s great cultural figures receiving a proper burial – at least in the foreseeable future.

“They don’t want Lorca found because obviously, if Lorca’s remains are found this will focus world attention on the poet and on what happened to the poet,” Gibson says, identifying the political right as the problem.

“Lorca is the maximum symbol of the victims of Franco’s war, so they won’t look for him and I think this is terrible for him, for Spain, for the family, for everybody, because we want to know the truth. I think it’s terrible that this man who is the greatest Spanish ambassador of all time, who’s done more for Spain than anybody else, you might say, who’s loved around the world and admired and appreciated, that they’re not looking for him, that the stateisn’t looking for him.”

Lorca’s voiceless legend

But where he is buried is not the only mystery surrounding Lorca. The fact that no recordings have been unearthed of his voice baffles Gibson.

“Of all the poets of his generation, he was the one who most recited his work,” he says. “He was an actor, he was able to be the part. But it’s astonishing that this man’s voice has not been found.”

And before he heads back through the cacophony of mid-morning central Madrid to continue work on his Buñuel biography, Gibson recalls with a chuckle one of Lorca’s many talents: “He had a great gift of listening to people – in a country where hardly anyone listens.”

Hasn’t Gibson also written a bio of Antonio Machado? That would have been worth mentioning in this context, but anyway I find this article true, inspiring, almost parabolic. Great job, Guy. Thanks a lot from a reader.

Candide, Many thanks, glad you liked it. Yes, Gibson did write a well-received biography of Machado – Ligero de equipaje – (as well as many other books). I didn’t mention Machado simply because, at the risk of putting words into Gibson’s mouth, Lorca (and Buñuel and Dalí) seem to be more important to him.

Thank you for this article. I also became obsessed with Lorca when I decided to include him as a character in my last novel.

I knew him, of course, I am from Spain and Lorca’s poems and plays are part of our culture. But Lorca’s life was never discussed when I was growing up. I learned about him through Ian Gibson’s biographies, Leonard Cohen’s songs and foreign movies like Little Ashes.

And now I read everything I found about him.