It’s over half a century since the artist Waldo Díaz-Balart left Cuba. On January 1, 1959, he was seeing the New Year in at Havana’s Tropicana nightclub with the son of President Andrés Rivero Aguero, when he heard the news that the Revolution had triumphed.

The 27-year-old Díaz-Balart knew he had to leave the island. His father, Rafael, had been a minister in the Batista government and had already left for the United States. His situation was also uncomfortable for social reasons: his sister, Myrta, had been married to a young man called Fidel Castro. They divorced in 1955.

“On the one hand the Balart family had been in power and on the other, my sister had been married to Fidel Castro. I knew I wouldn’t be free if I stayed on the island,” Díaz-Balart tells Iberosphere. “If they didn’t kill me they were going to throw me in jail.”

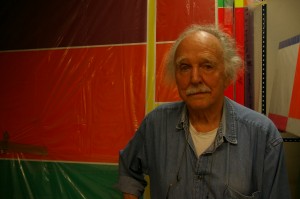

He is speaking in his modest studio-apartment in central Madrid’s literary district, a few blocks from where Miguel de Cervantes once lived. Now 80, he is charming and entertaining company and he still exhibits his paintings, which have the geometrical exactness of the “concrete art” movement.

Díaz-Balart’s first destination when he fled Cuba was New York, where he would spend the next decade. He had studied and practiced accountancy in Havana, but despite the trauma of being forced to leave his home country, the change helped him become a dedicated artist.

“You leave an entire life behind. But in my case it was, selfishly speaking, a liberation,” he explains. “I could be free and begin my artistic career. Before that, I was just a dilettante.”

New York in the sixties was a fertile place for any artist. With the counter-culture taking off, it was particularly stimulating for a young Cuban just discovering the city. He met the Velvet Underground and featured in two Andy Warhol films, The Life of Juanita Castro (a satire of the Cuban Revolution) and The Loves of Ondine.

“I was friends with Andy Warhol, as much as being friends with him was possible,” Díaz-Balart, says, remembering how wary he was of the celebrated pop artist’s capacity for manipulation. “Andy even suggested we do some paintings together –like he did with (Jean-Michel ) Basquiat – but I didn’t feel we had enough in common to do that.”

Seeking European inspiration, in 1970, Díaz-Balart moved to Spain. Despite finding himself back in a dictatorship, this time the tail end of the right-wing Franco regime, his art flourished, leading to a first major exhibition in 1972, at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo.

An Old-World Cuban

“When I moved to Madrid I realized that I was part of the concrete movement,” he says.

Concretism developed between the 1930s and 1950s, from the work of the futurists and the De Stijl movement. It is rooted in a highly European conception of art and, with its deliberate lines and colours, is perhaps the polar opposite of the spontaneity of the abstract expressionism of Americans such as Jackson Pollock.

Despite his Cuban origins and formative years in the United States, Díaz-Balart sees himself as an Old World artist.

“My mentality is very European, I don’t have the pragmatism of the United States,” he says. “Greek culture talks about the search for oneself, within oneself. And ‘concrete art’ is so called because it has no references outside of art itself.”

In honouring him as a Florida International University Frost Art Museum fellow in 2002, Cintas Collection curator Isabel Block Flefel wrote that Díaz-Balart “expresses and communicates to us his reactions and feelings on art in a geometric-abstraction form, but with an aesthetic order in his works.”

Geometry is a constant presence in his paintings, their mathematical precision and deceptively straightforward appearance reflected in names such as Módulo 3×3, 1.3.5.5.8.

Apart from spells in Paraguay, Brazil and Belgium, Díaz-Balart has been in Spain for the last 40 years. You would expect that a life so fully dedicated to European art in the Bohemian heart of Madrid would somehow distance him from his roots. But this native of Holguín insists he feels “100 percent Cuban” and he avidly follows current affairs, both in the country of his birth and around the world. Perhaps that is not so surprising given that members of his family remain deeply involved in politics: his nephews Lincoln and Mario Díaz-Balart have both had careers as Republican congressmen representing Florida.

Fidel: “an authoritarian guy”

Waldo’s memories of his former brother-in-law are brief, but not favourable. “If you adored Castro, then you were his friend,” he says. “Fidel was always an authoritarian guy.” He remembers Raúl Castro with a shade more fondness. As students, Díaz-Balart and his older brother Frank shared living quarters with the Cuban president in a Havana hotel.

“My contact with Raúl was sporadic, because he was already involved in his activities with the Communist Party. We were friends – we were the same age – but each of us kept to ourselves.”

Cuba has been difficult to ignore in Madrid in the last couple of years, with the island’s government sending freed members of the Group of 75 dissidents to the city, following an agreement with the Spanish authorities. For fellow exile Díaz-Balart, Spain’s relatively soft stance on Cuba is mistaken and the arrival of the ‘liberados’ has been painful to watch. However, he can’t help but see their plight with the perspective of a well-travelled artist.

“It hurts me to see what is happening in Cuba,” he says. “The government is using the poor freed Cuban prisoners in the same way that Andy Warhol manipulated people.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.