“Why are you interested in learning Arabic?” the teacher probed. It was a question intended to get us talking, to introduce ourselves and explain why we had chosen to give up two hours of our lives twice a week to sit in a drab high school classroom in Palma de Mallorca.

For travel, said some of my classmates; an interest in Arabic culture and music, answered others. A few wanted to learn the mother tongue of a husband or wife. The first two of those reasons were also in part my own. But I also had other motives: “Because of the world we live in,” I said.

As a journalist writing about Spanish and European politics and social issues for the last decade, I have borne witness to the growing importance of what goes on along the Mediterranean’s southern and eastern shores to the politics, economics and social attitudes in the countries north of that sea.

The lands of North Africa and the Middle East have sent millions of immigrants to work in Europe’s cities, factories and fields, breadbasket nations such as Morocco keep European supermarket shelves stocked with peppers, tomatoes and chickens, while Algerian and Libyan gas and oil keep the heat on in European homes and cars on the streets. Conversely, European companies have invested heavily in North Africa, attracted by cheap labour, geographic proximity and an increasingly educated workforce with a seemingly innate aptitude for foreign languages. French IT firms now operate call centers out of Tunisia and Morocco, British ones favour Egypt, while European manufacturers have shifted large swathes of production to the region. Millions of European tourists visit North African and Middle Eastern beaches, cities and souqs each year, while, back in Europe, interest in Arabic culture, music, literature and art has spawned multicultural festivals from Barcelona to Berlin.

Trade, investment, tourism, cultural curiosity and political cooperation in the myriad summits, conferences and forums that have sprung up in recent years are one thing. But, as anyone who has not been living under a rock will recognise, on the ground – both in Europe and in the North Africa-Middle East region – this blending of civilisations has often been far less sanguine.

Islamist terrorism has spilled blood and spawned anger from Casablanca to Baghdad and from Madrid to London. The spread of militant Islam among increasingly politically assertive Muslim communities in European cities has led to scaremongering about “Eurabia” and the “Islamisation” of Western culture. And economic immigration has sparked its own backlash, particularly among lower income sectors of society where competition between European natives and foreign workers for jobs and social services is fiercest.

It takes two to integrate

With uninspired monotony, politicians, among them many on all sides of Spain’s myriad political divides, talk of integration as the key to solving the social tensions that have arisen in European cities. In their view, the friction caused by immigration can be reduced or eliminated by providing (or imposing) language classes for immigrants, telling them to study and abide by local cultural customs and ensuring a carefully managed ethnic blend in public schools. However, such a top down approach, with the onus on the immigrant to do all the work can only go so far.

An immigrant made to feel unwelcome by the native population is hardly likely to have the desire – or even the chance – to cross cultural barriers, build relationships and integrate into that society. Discrimination in the labour market compounds the problem. Regardless of what EU and national anti-discrimination laws dictate, it is undeniable that in Spain, as in much of Europe, someone called Mohammed or Hassan usually has a harder time getting a job in the same conditions as someone named Juan, Manuel or Pedro.

It is therefore understandable that the North African and Middle Eastern immigrants who come to Europe tend to cluster among themselves. Many never move out of usually low-income neighbourhoods where they feel comfortable surrounded by their fellow countrymen and coreligionists. Hence the Kreuzberg district of Berlin is known as “little Turkey,” Brussels’ Molenbeek area boasts 21 mosques for a population of less than 80,000 and Lavapiés in Madrid has become synonymous with kebabs, Arab cafes and Halal butchers.

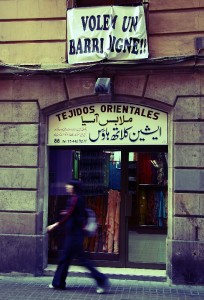

Even smaller cities have given rise to Muslim neighbourhoods. In Palma, about a half hour walk from the language school and far from the brash seaside resorts for which much of the Spanish Mediterranean is known, are a cluster of streets where the atmosphere is more Marrakesh than Magalluf, more Tripoli than Torremolinos, more Beirut than Benidorm.

Few native Majorcans do more than pass through here. Few linger to hear the call to prayer from the small local mosque, smell the fresh mint and spices in the stores or peruse the meat at a Halal butchers. And while some of them may visit Morocco, Jordan, Tunisia or Egypt on holiday next year, few will take the time to observe, let alone absorb, the enriching cultural diversity that now lies on their doorstep.

As a classmate of mine noted on a recent Friday evening spent strolling around the area: “People are afraid of what they don’t understand.”

As we move inevitably toward a more multicultural society, just a little bit of understanding on the part of native populations, be it a shopping excursion to a North African immigrant neighbourhood for spices, an afternoon in a Moroccan-owned tea room or picking up a few words of the Arabic language, can go a long way toward avoiding misconceptions and bridging cultural divides.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.