When is it appropriate for a public figure to resign? After displaying gross incompetence? In the wake of evident policy failure? Being caught up in criminal acts?

It’s not always clear-cut. Sometimes resignation is an option, but not necessarily the only one. An apology might be just as fitting, or a temporary withdrawal from front-line exposure to the limelight.

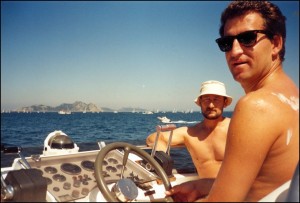

But in the last few weeks in Spain, there have been several cases that would seem to offer strong candidates for the sack. The most recent is that of Alberto Núñez Feijóo. On Sunday, El País newspaper published photographs showing that the Partido Popular’s premier of Galicia had been a good friend of Marcial Dorado Baúlde, who is currently serving a 14-year jail sentence for drug trafficking.

Despite Núñez Feijóo’s claims that he knew nothing of Dorado Baúlde’s misdemeanours at the time, when the two were close the latter had already been arrested for smuggling in a well-publicised police operation and it seems he was well-known in north-western Spain as an altogether bad egg.

With the Galician premier, who had been hotly tipped to succeed Mariano Rajoy as PP leader, confirming the veracity of the photos and the friendship, his position would seem to be in doubt.

Yet, when he appeared on Monday before the press, he insisted he will not be resigning over the revelations. His defence was simple: I’ve done nothing illegal.

Núñez Feijóo’s narco-friendship scandal broke as the PP’s Bárcenas slush-fund affair drags on, embarrassing the government somewhat, but without embarrassing it enough for anyone to step down or face any consequences.

Several senior PP politicians, including Rajoy, have been implicated in the illegal payments network that the Bárcenas papers seem to confirm, but none of them have resigned. Interestingly, the PP figure who has faced perhaps the most pressure to step down has been party number two, María Dolores de Cospedal, for her at times confusing handling of the media with regard to the scandal.

But there is also Finance Minister Cristóbal Montoro. His communications skills have never been in anything other than doubt, but his masterminding of an amnesty for tax dodgers last year seemed to make him even more susceptible to being replaced, especially as the initiative brought in only half the funds expected; and among the beneficiaries was a certain Luis Bárcenas.

Louis Vuitton and a whole lot more

And then there is Health Minister Ana Mato, who has ridden out allegations she received payments and gifts from the Gürtel kickbacks network, including holidays, Louis Vuitton bags and children’s parties.

“It hasn’t crossed her mind to resign,” friends of the minister told El Mundo in February.

The obvious way to put all this into perspective is to compare Spain with other countries – something Spaniards both love and hate to do in almost equal measure.

In February, the German education minister, Anette Schavan, resigned after it emerged she had plagiarised her doctoral thesis. In 2011, Defence Minister Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg stepped down after similar accusations.

In the UK, Culture Minister Jeremy Hunt resigned almost exactly a year ago over his alleged cosiness with the Murdoch media machine.

And in recent weeks, France has also seen a minister bite the dust, as Jérôme Cahuzac, head of the Budget portfolio, stepped down after a probe began into his holding of a Swiss bank account.

Meanwhile, back in Spain, no senior members of the government or the governing PP have resigned since Rajoy took power in December 2011. And yet, few would contest this is the most scandal-plagued administration since at least the mid-nineties.

With the politicians of the other parties seeming similarly reluctant to throw in the towel when the pressure mounts, the obvious conclusion to draw from all this is that Spanish politicians don’t resign. But the question is, why not?

The resignation trigger

It’s easy to make the generalisation that corruption is so deeply ingrained in the country’s political and social fabric that those in power feel less pressure than their counterparts in neighbouring countries to be called to account.

And yet, that’s too simplistic. Despite Rajoy’s insistence to the contrary, Spain does have a deep-rooted problem with corruption and side-stepping rules, from the ordinary folk who don’t pay taxes to the politicians who hand huge service contracts to companies that they then go and work for.

But other countries also have scandals – albeit not as many – and in those countries heads seem to roll. Their “resignation trigger” is much more sensitively calibrated than Spain’s. Can anyone seriously imagine a Spanish politician stepping down the way that Anthony Weiner, a US congressman, did after posting sexually suggestive photos of himself to a young woman?

The Weiner case may illustrate a broader point, that some countries are more prudish than others about certain issues – such as sex. But presumably the citizen of any country would view a close relationship between one of their senior politicians and a drug-trafficker as utterly disgraceful.

One argument for Rajoy not to sack any of his frontline colleagues is that if he replaces one, then why not half a dozen, given that a cloud hangs over so many of them? Another is simply that the Spanish prime minister instinctively prefers inaction to action.

But when looking at the deeper reasons for the lack of a resignation culture, the fact that Spanish politicians often get into the trade at an early age would seem to be a factor. Núñez Feijóo was only in his mid-thirties when he was holidaying on Dorado Baúlde’s boat, yet he was already deputy head of Galicia’s health service and then promoted to head of its national counterpart.

When someone invests so many years of their life in politics from such an early age, the stakes are that much higher – there’s not necessarily a clinic or law firm they can quietly return to should things not work out.

Valencia and absolution

But perhaps a stronger clue as to where Núñez Feijóo and his colleagues draw their refusal to countenance a swift exit can be found in Valencia.

The heartland of the Gürtel corruption probe, bloated and then deflated by the property bubble, the Valencia region is a financially mismanaged, corruption-ridden microcosm of many of Spain’s contemporary ills. And the architect of so much of this rot, former Valencia premier Francisco Camps, neatly summarised his approach to the job when, as investigations into his alleged acceptance of gifts from the Gürtel network continued, he declared: “The elections will absolve me.”

Camps, it should be pointed out, did eventually step down, although only when his trial was looming (he was in fact eventually absolved – by the judge). But the notion that winning elections legitimises more or less any kind of behaviour does seem to have taken hold among the political class, especially in parts of Spain where one party has a longstanding grip on power (such as the PP in Galicia and Valencia, or the Socialists in Andalusia). And Rajoy’s PP, remember, won the 2011 election with a landslide.

“We have realised that this country was more corrupt than we thought,” political scientist and commentator Fernando Vallespín told me. “We’ve passed from a Mediterranean moral consciousness regarding public ethics to a Scandinavian one. So in that sense we are judging with Scandinavian eyes – let’s say with Swedish eyes – what we did while we were Spanish.”

Except that, if you follow this logic, those in power don’t seem to have developed their moral consciousness: the electorate may be more Scandinavian, but the politicians are still Spanish.

Voters in the Valencia Community voted back into office people they knew were guilty of corruption. The politicians realized very quickly they could get away with it. The voters have to accept some of the responsibility.

There is a truism that has a number of variations but is basically that people get the government they deserve. However, I feel that Spain is hamstrung by pervasive self interested self serving cronyism, inherited from Franco. I worry that in spite of any outcry there seems to be no responsiveness, and accordingly little chance for change.