It is January 2003, I’m in the Ecuadorian capital Quito, and my arm is aching. I am holding a tape recorder up to Hugo Chávez’s mouth and he won’t stop talking.

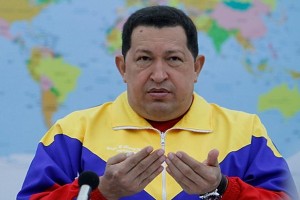

Chávez is in town to attend the swearing-in of Ecuador’s new president, Lucio Gutiérrez, a man many expect to pursue the same radical leftist path as the Venezuelan leader (although, as it turns out, he doesn’t). Other Latin American leaders have come to Quito, but Chávez is by far the biggest draw. I am part of a scrum of journalists who surround him as he strides into the lobby of a smart hotel, smiling and sure of his own magnetism.

I’m standing behind him, slightly to one side and I’d like to rest my arm by placing the tape recorder on his sloping, Bolivarian, shoulder but that seems somehow inappropriate.

Perhaps I’m also deterred a little by his reputation. Like many of the journalists around me in the hotel, and many members of the middle and upper classes in Latin America and beyond, I see Chávez primarily as a potentially dangerous figure who has allowed his country’s economy to nosedive and its political landscape to tip into instability.

After answering a couple of questions from the press, he goes on an improvised wander around the hotel lobby. He spots a young hotel employee, and homes in on him. Chávez strides over and starts chatting, shaking the man’s hand, patting him on the arm, asking about his job and quoting bits of homespun philosophy to him. The full force of Chávez’s charisma is focused on this youngster, who is spellbound.

It is quite a performance and quite suddenly, as I forget my status as a bourgeois westerner and put myself in the shoes of a working class, mestizo bellboy, I understand, at least a little, why millions of Venezuelans support Chávez and see him as a saviour.

In the week since Chávez died from cancer, a decade after that scene in Quito, I have recalled my only close-up encounter with him a few times. I have thought about it because it reminds me not just what a complex character he was, but also how commentators from across the political spectrum have failed to acknowledge this complexity or engage their intellect as they discuss his legacy.

“Hugo Chávez, a disastrous figure, has died,” wrote Salvador Sostres in Spain’s El Mundo. “He was disastrous for Venezuelans, disastrous for the free world, disastrous for humanity.”

Sostres goes on to attack the late president’s anti-Americanism, his “demented band of mariachis” and even his tracksuit, in an article that offers plenty of adjectives to illustrate how terrible Chávez was, but no actual evidence – and no sign that the writer has even thought very deeply about this man. Ironically, unalloyed critics of Chávez such as Sostres often end up using the kind of excessive language that he was so fond of when talking about him.

Figures such as Chávez tempt us towards Cold War-style stances – a black-and-white view of the world that labels things as “good” or “disastrous”, while closing our eyes to the often important shades of grey in between. Any serious appraisal of Chávez would have to include his faults, from his repression of unfriendly media and opponents to his taste in sportswear. But it should also accept that he was repeatedly elected into power by a majority, invested heavily in sectors such as health and education and just as importantly, gave the poor a voice.

His marathon televised weekly monologues, Aló, Presidente, were easy to ridicule as self-indulgent exercises that reinforced the Chávez personality cult. But wouldn’t even right-leaning Spaniards such as Sostres like to see Mariano Rajoy appear in public occasionally and explain at length his plans for the country?

Familiarity breeds blindness

Yet equally, there are those on the left who are also drawn into the trap of regarding a figure like Chávez from only one angle, usually the one that suits their politics. Tariq Ali’s various meetings with the man over the years seem to have left him blissfully unaware of the Bolivarian leader’s shortcomings, and he writes in The Guardian:

“If I had to pin a label on him, I would say that he was a socialist democrat, far removed from any sectarian impulses and repulsed by the self-obsessed behaviour of various far-left sects and the blindness of their routines. He said as much when we first met.”

The students, journalists, businesses and others who suffered during Chávez’s 14 years in power would not recognise the man from that description, from which you might draw the conclusion that familiarity breeds intellectual blindness.

Today’s ocean of media and internet outlets, forums and comments sections means that a huge array of opinions can – or should – be represented on more or less any subject. And yet, the shouty, one-track voice often dominates. And as readers we face the temptation to search for the opinion that chimes with, rather than challenges, our own, without bothering to go deeper.

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve changed my view of Hugo Chávez over the years, which might make me weak and wishy-washy, but I’m comforted by Felix Salmon’s motto that “if you’re never wrong you’re never interesting.”

And sometimes the subtlest, most insightful views come from unexpected places. Gabriel García Márquez remains a close friend of Fidel Castro and has deep leftist sympathies. At the very start of Chávez’s presidential tenure, the author of The Autumn of the Patriarch sat next to him on a flight from Mexico to Caracas and took the following view:

“As I watched him walk away, surrounded by his guards with all their military decorations, I had the odd feeling that I had travelled and talked with two quite separate men. One was a man to whom obstinate good fortune had given the opportunity to save his country; the other was an illusionist who could well go down in history as yet another despot.”

Saviour, illusionist, despot: the difference is not always as clear as we’re told.

A good summary.Chavez will never be understood by Europeans and North Americans because of simplistic press reporting.To the world outside Latin America he will remain an enigma.

I didn’t read the article by Salvador Sostres from the El Mundo newspaper that he supposedly wrote on the death of Hugo Chavez, but being part of the pathetic mass media in Spain, it isn’t surprising that he wrote what he did [whatever that was]. In Spain, unless you visit some of the non-conventional Internet media sources, never expect to read, watch, or hear any information coming from any and all conventional media that’s adhered to the truth or free from bias. The fact is that all mass media in Spain is under very tight control and the only acceptable type of “journalism” here is that which protect the status quo. There are no real journalist in Spain, only prostitutes.