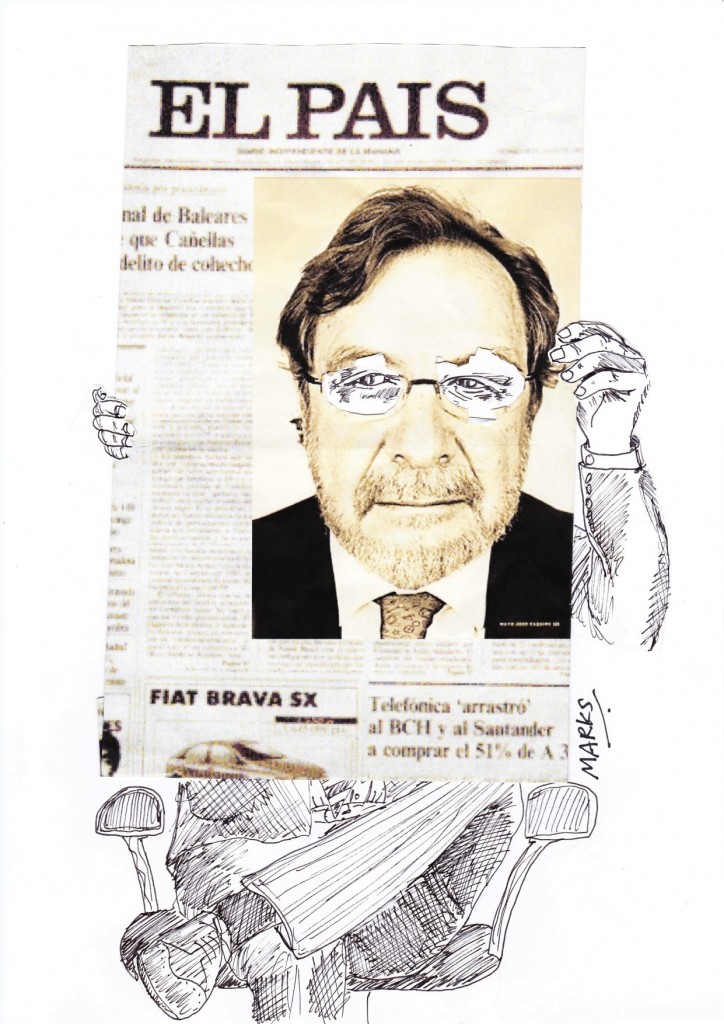

In November 2010, Juan Luis Cebrián, the founding editor of El País, and CEO of the Prisa Group, the media empire to which the newspaper belongs, announced the sale of 70 percent of Prisa for €900 million to a New York-based investment group

The reason for the sale was a €4.7-billion debt he had created after an expensive foray into pay-TV was followed by the financial crisis and a downturn in advertising. At the time of the sale, Prisa’s debt was more than 12 times its withered stock market value.

The sale spelled the end of Cebrián and the Polanco family’s control of Spain’s leading media group, which had been founded on the success of El País over more than three decades. “Better 30 percent of something than 70 percent of nothing,” said Cebrián at the time, ominously promising “deep change”.

Nicolas Berggruen and Martin Franklin, who lead the investment group that now controls El País future, say they have no interest in exercising editorial control over the paper. They have also bought into French daily Le Monde. “We look for high-quality companies that give us the opportunity to invest capital on an opportunistic basis. Great company, bad balance sheet is the motivation,” Franklin told The Guardian newspaper in 2010.

The investment group’s aim is simple, to increase the share value of Prisa; in short, to make the group profitable and sell it on, as Berggruen did with Media Capital in Portugal, selling it to Prisa in 2005. And one very quick and simple way to make a company profitable is to reduce the workforce and lower the wages of those who remain. The other way is to sell off less profitable divisions: publisher Alfaguara is currently looking for a buyer.

Fast forward to early October of this year, when Cebrián announced that he would be sacking 128 of El País’s staff of 464, and sending 21 others into early retirement. The survivors would have to accept a 15-percent pay cut. Thanks to the new labour laws, the cost of shedding one third of the paper’s workforce is half what it would have been in 2011.

Cebrián says that the paper, which had made a profit since the get go, has been losing money since August and that revenue is down €200 million since 2007. Sales are expected to fall 10 percent this year to 320,000.

So where is the new, meaner, leaner, El Paísheaded? Journalists have threatened to strike, while Cebrián says that either the paper restructures and finds a new business model, or it’s finished.

Perhaps a clue as to that new business model is to be found in El Huffington Post, the Spanish-language edition of the digital daily founded by Arianna Huffington, and in which Prisa has a 50 percent stake.

It has a team of seven journalists, and, like its US-based original, relies on “citizen journalists” and bloggers and other contributors to provide free content. Readers may remember that when Huffington sold the Huffington Post to AOL for $315 million she was accused of exploiting journalists who said that they had contributed to the paper’s huge readership and profitability.

In recent years El País has used growing numbers of young journalists that have graduated from its own journalism school to produce copy, particularly for the paper’s voracious website, paying them a pittance. But in a country where thousands of journalists have been sacked in recent years, and where newspaper sales have fallen sharply, young hacks will accept such conditions to get their name published.

Interestingly, as a result of this influx of young writers, the paper’s writing style has become somewhat more accessible than before, although it is all too often clear that the youngsters do not really know their subject to the same depth as their forebears did. But perhaps that simply reflects the belief on the part of the paper’s editorial team that it has to reach out to a younger readership that is less interested in the background or the big picture.

And what of the future of Juan Luis Cebrián after he stands down as CEO? He has been accused of losing his grip over Prisa, perhaps distracted by his frequent trips around the world to comment on the future of the media and his prolific output of novels and essay collections.

For all his “the future is digital” talk, Cebrián is a dyed-in-the-wool newspaper man and still insists he can turn El País round and increase its sales. He may not be wrong. Berggruen and Franklin said at the time of their purchase of 70 percent of Prisa that they believed print media still had a future, albeit in a much smaller market. In Spain, as Abc and El Mundo teeter on the brink, and left-wing rival Público has already gone to the wall, El País could be the last man standing, albeit a shadow of its former self.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.