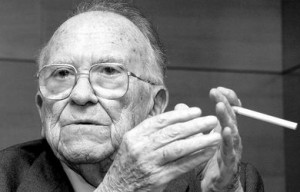

Santiago Carrillo, who has died at the age of 97, belonged to another time, or perhaps more accurately, and depending on one’s age, to a number of other times: the Civil War; the decades of exile during the Franco regime; the first years after the death of the dictator; but above all to a time when people still took Communism seriously.

Despite his failure to secure a lasting place for the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) in Spanish political life, he managed to reinvent himself as one of the guardians of that most revered institution, the transition to democracy.

While still in his teens, as a member of the Socialist Youth, Carrillo took part in the uprising in Asturias in 1934, and was jailed in November of that year until February 1936. Immediately after his release he travelled to Moscow and became a member of the Communist Party.

Taking advantage of the power vacuum created in the immediate aftermath of the military coup led by Franco and other officers in the summer of 1936 when the Republican government fled Madrid, the Communist Party took control of the now besieged capital.

Aged 21, Carrillo was placed in charge of public order in the cpaital. In late November of 1936, with the Nationalist forces seemingly set to break the siege, some 5,000 prisoners suspected of sympathies with Franco’s forces, were taken from jails in the capital and relocated further behind the Republican lines. During this process, an estimated 2,000 — some put the figure at 4,000 or higher — were shot and dumped in mass graves.

Carrillo has always denied any responsibility or involvement in the killings, but the so-called Paracuellos massacre would dog him for the rest of his life after he returned to Spain from exile in 1977.

By early 1939, with Franco’s forces now in control of most of the country, those holding out in Madrid were increasingly split. The Socialist Party wanted to negotiate a surrender with the Nationalists, while the Communists wanted to hold out, knowing that war between France, Britain, and Nazi Germany was imminent.

Carrillo fled Spain for France, from where he took part in the abortive assault on the Aran Valley in 1944, still hoping that the Allies would invade Spain and kick Franco out.

After the end of the Second World War, and the gradual integration of the Franco regime into the international community, Carrillo, like so many others wrongfooted by events, might reasonably have been expected to disappear, consigned to a footnote in the history books.

Never say die

Instead, he launched a new political career. Spending his time between Moscow and Paris, Carrillo consolidated his position within the Communist Party in the post-war years. At this time, the PCE’s Secretary General was Dolores Ibarruri, aka la Pasionaria, and the second-in-command Vicente Uribe, a man Carrillo considered an arrogant drunk. But Carrillo was still in his thirties with only six years’ membership in the party, and thus not yet a leadership candidate in an organisation which respected seniority.

Aware that Pasionaria in Moscow could make or break careers, as well as issue death sentences, Carrillo bided his time in France, although the Spanish Communist Party was illegal there after 1950, working in his office 12 hours a day. Carrillo’s many enemies have accused him of treachery, betrayal, and murder, but never of laziness.

Finally, with the backing of Moscow, Carrillo took over the exiled PCE in 1960, organizing opposition to the Franco regime, and sending undercover activists to Spain to infiltrate labour unions.

At this point Carrillo was still a loyal servant of Moscow, but by the end of the decade he had freed the party from Soviet control, becoming the best-known exponent of Eurocommunism, and unveiling his new strategy at the PCE’s Seventh Congress in Paris in July 1965. By now membership was growing, and there were a substantial number of delegates from within Spain, including Marcelino Camacho, the leader of the illegal trade union, Comisiones Obreras. Carrillo’s report to the congress was the basis of his book, Después de Franco, qué?

During this time, while cautiously acknowledging the economic boom underway in mid-sixties Spain, Carillo still clung to the notion that the dictatorship could be overthrown by a series of peaceful strikes and the support of a largely conscript army – as would happen in Portugal in 1974.

He would publish a stream of books over the next dozen years, culminating in Eurocommunism and the State in 1977. They were all widely distributed and translated, giving him for the first time a reputation outside his own party: he no longer considered himself a party bureaucrat, but a theoretician, read and cited within the European Communist movement.

Thus, from 1967 on, Carrillo advocated an “alliance of labour and culture”, trying to broaden its appeal to the professions: in contrast to most European Communist parties, the PCE warmly embraced the student revolt of May 1968, an event that had enormous repercussions in Spain.

The Transition

Franco’s death in November 1975 speeded up the process of political change, forcing Carrillo to face harsh new political realities. The dictator had already appointed Prince Juan Carlos as his heir.

Spain was eager to gain entry to the Common Market and the more forward thinking politicians, military and clergy who had served Franco knew that this would require some kind of Parliament, recognition of the right of association, and the release of political prisoners.

Meanwhile Carrillo was trying to position himself as the kingmaker, the man who would negotiate, as the representative of the workers and intellectuals, with progressive elements in politics, the army, and the church.

Little wonder: on the eve of the country’s transition to democracy, the Socialist Party still had no political influence. But at the Socialist Party’s congress at Suresnes in 1974, the Socialist International recognised a new leadership based on a small nucleus of lawyers from Seville, among them Felipe González. That said, the PCE had a hundred times more members in Spain than the Socialists, (PSOE).

Over the next two or three years, directing operations from France, Carrillo would fight hard to establish a role for the Communist Party in post-Franco Spain: it would join an ill-fated Democratic Junta in 1974 shunned by the PSOE and the nationalist parties, which formed a rival broad front the following year, with both merging in 1976. Until 1976, Carrillo had demanded a break with the old regime, through mass activity, but that perspective was now quietly abandoned. Now, Carrillo, who had always opposed the return of the monarchy, realised he had no choice but to accept having to include King Juan Carlos in his plans.

In July 1976, Juan Carlos appointed as prime minister Adolfo Suárez, who moved quickly to dismantle the regime’s fascist structures and prepared for elections in 1977. To do so he needed the cooperation of Carrillo, which was readily forthcoming. But the PCE remained illegal, and when the government refused to allow its Central Committee to meet in Madrid, Carrillo staged a publicity coup by having it meet publicly in Rome in July 1976.

Carrillo also made political capital out of the murder in January 1977 of a group of lawyers who were sympathisers of the PCE. The killings may have been intended to provoke retaliation and an intervention by the army, but in the event, the party’s response of calling massive peaceful demonstrations supported by wide sections of the population impressed most Spaniards. He made sure that the party showed itself as important, prudent and disciplined.

Fearful of being sidelined by fast-moving events, Carrillo decided that he must be in Spain to lead the transition personally. In February 1976, carrying forged papers and wearing a wig, he secretly crossed the border. Once the police detected his presence the government faced a dilemma, as it dared neither to arrest him nor grant him legal residence.

But Carrillo was worried that things were slipping out of his control, as the leaders of other political tendencies were working openly, while he was not. More alarmingly, other PCE leaders who had been in Spain longer were taking day-to-day decisions. Carrillo broke the deadlock by calling a press conference attended by 70 journalists in Madrid on December 10. He was arrested 12 days later, but freed at the end of the month. He knew that his rivals in the PSOE would be unable to reach agreement with the government without him: his control over the PCE was consolidated. However, the PCE remained illegal and the PSOE, backed financially by the German Social Democrats, was preparing for parliamentary elections.

At a secret meeting between Suárez and Carrillo in February 1977, both men discovered they had much in common. Suárez had accepted the structures derived from fascism as a fact of life, rather than as revealed truth. Carrillo saw himself as a political thinker, but his Marxism-Leninism was always a convenient tool, not a guide to action. The two men became the main architects of the transition to a parliamentary monarchy.

Clutching defeat from the jaws of victory

The PCE was to be legalised, but under Suárez’s terms: abandoning the overthrow of capitalism and the demand that the opposition should be part of a provisional government. Suárez was to be left free to oversee the transition. But the agreement, which at that moment seemed the zenith of Carrillo’s career, would soon lead to his political demise.

Still rooted in the ideas of the Civil War era, the PCE’s dogma was that Spain was ruled by a narrow clique of landowners and bankers. Carrillo still refused to accept analyses of Spanish society that showed the emergence of a middle class and an aspirational working class.

Once back from exile, Carrillo soon realised that things were more complicated: the country was not run by a clique, but a broad middle class that was trying to dismantle an authoritarian state while ensuring its own survival in the face of massive unrest.

Instead of addressing this new reality, Carrillo underwent a dramatic conversion and became a cheerleader for Spain’s modernised capitalism. The problem was that once the struggle for socialism and a republic was abandoned, the party became redundant.

At its April 1977 meeting the PCE’s Central Committee was told by Carrillo that the party now recognised both the monarchy and its flag. Its members were given reasons why the party’s traditional principles had been abandoned, but were not told about Carrillo’s secret negotiations with Suárez. Most of the membership had joined over recent years and were in no position to challenge Carrillo, who was able to retain his control of the party.

Carrillo now focused on elections in two months’ time. The problem was that its programme hardly differed from that of the PSOE, which became its main rival. Carrillo hoped for a broadly based coalition government which would include capitalist parties, Socialists and Communists, but failing that, he wanted a UCD conservative government supported by the PSOE and the PCE. The break with the past was quietly forgotten, as it became accepted that the population was to take no active part in the transition.

At this time the PCE claimed to have 150,000 members and its weekly journal, Mundo Obrero, had a circulation of more than 200,000. The party was immensely dynamic and, released from the restrictions of working under cover, threw itself into the election campaign. Day-to-day work in trade unions and neighbourhoods was neglected, while election meetings attracted enormous audiences where those daring to display republican flags were beaten up by PCE stewards.

In the elections on June 15 Suárez’s UCD came top with 34.3 percent of the votes; the PSOE garnered 28.5 percent. The PCE got just over 9 percent. Carrillo always denied that the result was a disaster, describing it as very positive for democracy and the forces of the left. But the reality was that Suárez had passed his first hurdle by avoiding the formation of a provisional government.

Over the term of Suárez’s government, the PCE was riven by internal arguments between reformers and hardliners, and Carrillo’s hold gradually weakened. When Suárez was forced to stand down in January 1981, Carrillo lost his only political ally.

In the elections held that summer the PCE won just 3.6 percent of the votes and was reduced to four MPs, one of them Carrillo. But Carrillo refused to stand down or hold a special party congress to consider the situation. The wily political survivor believed he could emerge strengthened from the disaster. But now, for the first time, his own position was threatened.

When the party executive met in November 1982, Carrillo realised that the election defeat had been so disastrous that he would be unable to carry on as before, and on the third day of the meeting he announced that he was giving up as General Secretary in favour of Gerardo Iglesias, an obscure organiser from Asturias. Carrillo avoided criticism or debate over his responsibility for the party’s debacle. He stayed on the executive, made no criticism of his own performance, and continued as parliamentary spokesman.

Carrillo hoped he could continue to rule behind the scenes, and eventually resume the leadership. But Iglesias betrayed Carrillo by making peace with the reformists. Carrillo retained his seat in Parliament, but could not accept a subordinate role and formed his own faction.

Endgame

As the government, now freed from any substantial opposition on its left, pressed ahead with neo-liberal policies and intensified its support for NATO, the PCE was unwilling to resume the mass mobilisation which had been abandoned in 1977, yet could find little political space between the PSOE and the UCD. Meanwhile there was a continual tide of defections, mainly to the PSOE, while the PCE vote in provincial elections continued to fall.

In 1986 Carrillo formed a new party, the PTE, which failed to win a seat in parliament in the elections of that year. In 1991 he negotiated entry into the PSOE for all PTE members except himself, finally recognising that the future of Spain’s left lay with the party he had abandoned in 1936. The PSOE, always short of cadre, welcomed the new recruits and gave them posts in the party and administration, but the return of the former secretary of its youth group would have been too much of an embarrassment.

Carrillo’s political life was over, although he had earned himself a place in public life as the man who had selflessly helped steer Spain from dictatorship to democracy. He stuck to the story that his party’s disastrous fate was due to a combination of objective circumstances and the idiocy of those who had opposed him, and few could be bothered to argue.

As Trotsky said of the Stalinists support for the Popular Front government during the Civil war: (it was) “an alliance with the shadow of the bourgeoisie.” Carrillo followed that policy all his political life including during the transition to Spanish democracy and ended his life being praised by the King who was placed on the throne by a fascist.