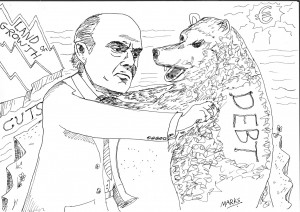

The story goes that right up to the day Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy appointed him economy minister, Luis de Guindos was unaware that he was to be landed with the job of repeating for six months that Spain didn’t need a bailout before eventually taking part in the “victory”— as described by Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy — of accepting the European Union’s offer of up to €100 billion to keep Spain’s banks afloat for a little longer.

The story goes that right up to the day Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy appointed him economy minister, Luis de Guindos was unaware that he was to be landed with the job of repeating for six months that Spain didn’t need a bailout before eventually taking part in the “victory”— as described by Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy — of accepting the European Union’s offer of up to €100 billion to keep Spain’s banks afloat for a little longer.

Until last December, the 52-year-old De Guindos led a quiet life, mainly employed as the director of the PwC Centre for Finance at Madrid’s IE Business School, while enjoying the benefits of sitting on the boards of several companies, among them Endesa Chile.

Few may have known his face before he took up the job of sorting out Spain’s finances, but De Guindos isn’t really the man from nowhere: he already had experience in government before accepting Rajoy’s poisoned chalice. From 1996 to 2004, he worked in the Economy Ministry under Rodrigo Rato — who would go on to be managing director of the IMF — holding several positions, among them secretary of state for economic affairs and secretary of the economic affairs commission. Between 2006 and 2008, he was CEO of Lehman Brothers for Spain and Portugal.

De Guindos may not have been Spain’s best-known economist, and he may not have wanted the job: the rumour mill says he had his eye on becoming governor of the Bank of Spain — in the end he had to settle for forcing the early and ignominious exit of Miguel Ángel Fernández Ordóñez, after publicly blaming him for the Bankia fiasco — but he had long been in the running to take on the top post in the Economy Ministry, having put together the Partido Popular’s economic program for the 2004 election, which the party was set to win, until Islamic terrorists bombed several trains in Madrid.

Which is why he then went on to work at Lehman Brothers, where he managed to discreetly row away from the doomed vessel within seconds of the subprime torpedo hitting it, a catastrophe that set off the current global banking crisis and that lost Spanish investors alone around €1 billion.

The “keys to prosperity”

The Spanish media has in the main chosen not to dwell on this unfortunate smudge on Mr De Guindos’s otherwise impeccable CV, nor on his close and long association with Rodrigo Rato, considered by many to be responsible for the mess at Bankia, and whom he reveres. There hasn’t been much talk either of the book he edited, España, claves de la prosperidad (Spain, the keys to prosperity), published by the PP’s think tank, FAES, in which he summarizes in glowing terms the PP’s two terms in office under José María Aznar, during which Spain entered the euro, and the construction boom began that after a decade of unbridled speculation and financial hooliganism finally brought down the economy in 2008.

De Guindos is one of the privileged few in Rajoy’s circle of trust, and has spent many an afternoon explaining to the prime minister the finer points of macroeconomic management. He also speaks English fluently, so will be able to explain the jokes at EU summits to his boss. As a lifelong Atlético de Madrid fan, he will also know a thing or two about financial mismanagement, as well as the virtues of suffering.

A liberal, it will come as no surprise to learn that he is a devout follower of Austrian school guru Friedrich Von Hayek: so just in case anybody hadn’t caught on yet, Spain with De Guindos holding the purse strings isn’t going to be spending its way out of the crisis.

In an interview with the Financial Times shortly after he took up the post of economy minister, De Guindos was asked how he intended to achieve growth and job creation at the same time as austerity. He ignored the question, instead spelling out the need to send the right signal to the markets by cutting public spending so as to reduce the deficit. Later in the interview he reveals the secret to job creation: “modification of the system of collective bargaining.” It might be said that Spain’s labour market is largely dysfunctional, with a privileged group of haves protected by generous contracts, and a huge group of have-nots working long hours for low wages on no contract or junk, short-term contracts. The plan now is to move very quickly toward a US-UK style labour market.

In the interview, the FT’s Victor Mallet gamely returns to the question of how to combine growth with austerity. It’s worth reproducing De Guindos’ stonewalling in full: “I think we have to stress the importance of these reforms and their potential. I think these reforms might produce in terms of confidence, and very rapidly, positive effects on the Spanish economy, and afterwards this commitment to austerity will create confidence in the marketplace. We cannot afford to go to the markets and say that, well, Spain is not going to be an orthodox campaign in terms of fiscal policies and in terms of reforms. This is something that would be extremely detrimental to the perception of the Spanish economy and extremely detrimental to the single currency. So it’s not only a national commitment, it’s also our main contribution to the future of the single currency.”

A victorious rescue?

Along the way, he wants to sort out the country’s banks. Which brings us to Bankia, the catalyst for the EU “victory” rescue.

Last month, De Guindos and Rajoy carried out the biggest financial bailout since the outbreak of the economic crisis. Bankia, the giant which resulted from the merger of seven savings banks only a year and a half ago, was nationalized through the conversion of a €4.5-billion holding of preferential shares into equity.

Spain has been through banking crises before, notably Banesto in the early 1990s, but never has an economy minister been given such leeway as De Guindos, who has sidelined the Bank of Spain, embarking on a de facto nationalization program, administering tax payers’ money to keeping banks afloat, and sorting out the banks’ toxic assets, while sacking and replacing board members, seeking only the advice of the country’s banking elite.

Bankia has put Spain’s financial system under scrutiny from investors and analysts worldwide who worry about the country’s ability to strengthen its banks while adopting harsh fiscal consolidation policies in the midst of a recession. In the light of this, and the CAM savings bank debacle, the Spanish tax payer is increasingly asking: who is responsible for this mess? Might it be the very politicians who are trying to get us out of it?

De Guindos has been asked repeatedly about the government’s plans to investigate and identify those responsible for Bankia’s downfall and subsequent nationalization. His poker-faced response so far is: “we have not identified any responsibility.”

Similarly, he is sticking to his story that he will have to wait for the results of an audit of the country’s banks before deciding how much of the €100 billion on offer he will accept, insisting that this is no rescue, but “a loan on favourable terms” for banks that need help.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.