When friends or family come to Spain to visit and ask me to name the sites they should see in and around Madrid, they’re always surprised when I put a monument to fascism near the top of the list.

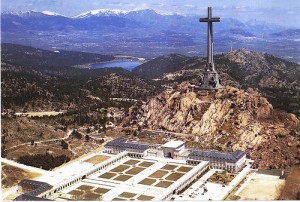

But there’s no denying it, El Valle de los Caídos, or the Valley of the Fallen, the resting place of dictator Francisco Franco, is an awe-inspiring place. You can see it from miles away, a 150-meter-high stone cross – one of the world’s largest – rising up out of a rocky hillside north of the capital. Beneath the cross a huge esplanade gives a view over a strangely peaceful, wooded valley. Go on a clear day and the blue sky is a breathtaking backdrop to the scene. Go there in rain or sleet and an eerie drama is more apparent.

The fact that the remains of Franco lie buried in a basilica beneath the famous cross is undoubtedly what lends this site much of its sinister nature. But a commission of experts, appointed by the government in May, has recently concluded that the Caudillo should be exhumed and buried elsewhere, as part of an effort to make El Valle de los Caídos a place of reconciliation.

This is clearly a worthy aim. Besides being a relatively popular tourist attraction, it’s also a magnet for far-right nostalgics, who like to gather there on the November 20 anniversary of Franco’s death to honour him, a disturbing notion, especially so when you remember that this is also a religious site, hosting a Benedictine monastery. It’s also important to remember that defeated Republican prisoners built El Valle de los Caídos, compounding its status as a monument to the victors.

“Blow it up?”

But how realistic is it to “de-Franco” the greatest monument to Franco that exists?

Utterly impossible, according to José Álvarez Junco, a historian at Madrid’s Universidad Complutense, who was asked by the government to form part of the commission. He turned down the invitation.

“This is Francisco Franco, this is the dictator’s tomb and it has the meaning it has and it was built under the close direction of the dictator,” he told me shortly after the commission was first appointed. “And it has all the symbolism. It is very important, very meaningful. The only way to convert that into a thing with a different meaning would be to blow it up.”

He points to the monument’s appearance as proof that its essence can never be changed. The huge cross and a Francoist eagle insignia on the front of the building clearly evoke nacionalcatholicismo, the far-right, deeply religious ideology of the Civil War’s victors.

Even the commission itself doesn’t seem to have been convinced about removing Franco’s body, with some members voting against the move. Franco’s own family has voiced opposition and, predictably, so have far-right groups, with one threatening to sue the government.

Besides this resistance, the experts’ recommendations, which also include offering more viewable data at the site so that it becomes more like an “information centre”, are almost certainly not going to be implemented. The report was commissioned by the Socialist government, which made broaching Spain’s historical memory a key part of its political agenda. But with the Popular Party (PP) romping to victory in the November 20 election (some think the choice of date was a Socialist attempt to scare voters into not backing the conservative PP), the report will almost certainly be put in a draw and forgotten about.

The PP has always been wary of the “Franco issue”, opposing the Socialist historical memory law as needless raking up of a painful past. With an economic collapse to avert, incoming Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy currently has another reason to ignore the Valle de los Caídos report.

But however politically divisive and impractical removing Franco from his tomb may be, ultimately it has to be a step Spain takes. Maintaining a site that disgusts many Spaniards while being revered by an extremist minority is hardly apt for a civilised country. El Valle de los Caídos is a breathtaking place – and one whose drama pays tribute to a repressive dictator who died of natural causes, rather than to the thousands who died in the war he unleashed.

In June, freelance journalist and Iberosphere contributor Nick Lyne visited the site of General Franco’s tomb outside Madrid to ponder its status in modern Spain.

Much like the ICTY was a necessary international effort to get a grip on the atrocities committed in the Balkans, Spain might need an international commission to be told what to do with the whole Civil War issue. This country seems incapable of doing it alone: efforts to do justice to the victims have come late and are plagued by partisan bias, making people here relive the horrors instead of coming to terms with them.

Having been the Civil War an internationalised conflict, why not internationalise the efforts to find it’s final place in History?

I, personally, would like to see Franco’s (and Primo de Rivera’s) remains relocated to tiny little graves in their home towns’ cemeteries, so as to take the homage to them out of the equation. Then the Valle de los Caídos will be there to overwhelm the visitors. It really gives you the creeps to stand under the cross and feel crushed and annihilated as an individual by the monumentality of the whole compound’s architecture.

Those who still like to feel like ants can never be convinced, anyway.