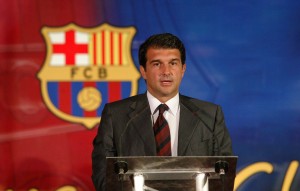

What do you do after making one of the world’s most successful football clubs even more successful? If you’re outgoing Barcelona president Joan Laporta, you think about going into politics. Catalan politics.

Bound by the football club’s two-terms-only rule, the 47-year-old will be out of a job by June 30, by which time Barcelona’s 100,000 members must elect a new president.

Press reports suggest that Laporta will announce his intention to run in the regional elections due in Catalonia this autumn. Over the last year, his political ambitions have gradually taken shape. He briefly flirted with the two main nationalist groupings, the Catalan Republican Left (ERC), and the conservative CiU, neither of whom see him adding value to their campaigns in the autumn elections in the northeastern region.

Undeterred, Laporta has set up his own platform, last week announcing the launch of his laporta2010.cat website to inform the electorate of his vision for Catalonia. Sadly, at the time of publication the site was still not up and running.

What we do know about Laporta’s plans for Catalonia is that he backs independence. He has led marches calling for self-determination, and supported a non-binding (and legally controversial) referendum in the small town of Arenys de Munt in December, in which more than 90 percent of those who voted backed separation from Spain (although turnout was only 40 percent). Further similar ballots followed across the region, however, polls carried out over the last decade suggest Catalans are actually more ambivalent about independence, with around 50 percent against it.

Guy Hedgecoe looks at Catalonia’s tense relationship with Madrid and recent ballots to bolster its campaign for independence from Spain in this dispatch for RTÉ’s World Report broadcast on December 13.

Surveys also suggest that Barcelona’s president would win up to 10 seats in the 135-seat Catalan parliament, but that he might increase his vote if he were to stand alongside Joan Carretero, a former senior figure in ERC who has set up his own pro-independence party Regrupament Independentista. Laporta and Carretero have publicly stated their mutual admiration, saying they share similar ideas. Surveys show that a Carretero-Laporta double whammy could garner up to 15 seats. ERC, meanwhile, which is part of the Socialist-led coalition in the region, could see its share of the vote fall to a similar number of deputies.

Popular, and populist

Laporta is undoubtedly a popular man in Catalonia, thanks to his performance at the helm of Barcelona FC. When he and his team of young Turks took over in 2003, the club had not won any silverware since 1999. He brought with him a new manager, Frank Rijkaard, and Brazilian wunderkind Ronaldinho. But there was a lot of dead wood in the side, and he and his untried and inexperienced board came under fire as the team struggled in the early stages of the season, at one point hitting the bottom of the table. But Barça rallied to close the season in second place. To his credit, Laporta also took on the notorious Boixos Nois neo-fascist fans, banning them from the Camp Nou. This prompted death threats and a kidnapping plot that came to nothing.

The following season, with new signings including Samuel Eto’o, Deco, and Edmilson, the side hit its stride, taking the league title; a feat it repeated the following season, adding the Champions League. After a two-season dip, Laporta replaced coach Rijkaard with Pep Guardiola, who has rebuilt the side to stunning effect. They have dominated Spanish football, winning the treble last season, and setting a pace that Real Madrid has only begun to match this season.

Laporta will certainly have picked up more than footballing skills during his time at Barcelona, and they will come in handy if he does embark on a career in politics. Chief among them is his demonstrable ability to handle pressure. He faced a no-confidence motion in 2008, with 60 percent of the vote going against him. Nonetheless, the naysayers were six percent short of the figure needed to hold a new vote, and the president refused to stand down. Eight of the 17 board members resigned in protest.

Laporta also emerged relatively unscathed from a 2005 episode which saw five members of Barcelona’s basketball side resign, accusing him of authoritarianism.

He shares at least one other trait demonstrated by a fellow political survivor. Like Esperanza Aguirre, the right-wing leader of the regional government of Madrid, Laporta has been accused of spying on his own people.

Last March it emerged that Barcelona’s director general Joan Oliver had carried out surveillance on vice-presidents Jaume Ferrer, Joan Boix, Rafael Yuste and Joan Franquesa. When the scandal blew up, six months later, Oliver denied it was espionage, calling it a “security audit” carried out for their protection, after Franquesa had said he felt he was being followed.

The four, backed by other board members, were among those under consideration to replace Laporta on a continuity ticket. Since then, only Ferrer remains in the running.

The Barcelona chairman shrugged off the affair, once again accusing the Madrid media of running a campaign against him.

Laporta knows that nothing goes down better in Catalonia than beating Madrid, both in the political arena and at football. His chances of success in the autumn elections will undoubtedly be given a major boost if he takes the Champions League for the second consecutive year, especially as the final will be played in Real Madrid’s home ground, the Santiago Bernabéu.

[…] place presents a tactical dilemma for the managers, Arsène Wenger and Pep Guardiola. Arsenal and Barcelona’s playing styles are very similar and it is unlikely that either coach will lean toward […]