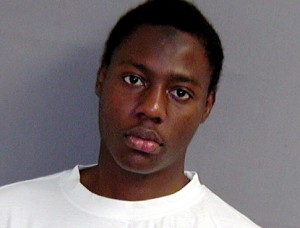

Ever since Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab allegedly tried to blow up a plane on Christmas Day with explosives hidden in his underwear authorities in the United States and Europe have been touting the benefits of installing body scanners at airports. It may be a new technology, but it is just the latest embodiment of an old debate pitting security against privacy – one in which Spain, as the current EU term president, has chosen to sit on the fence.

The privacy concerns raised by these machines are understandable: if they can be used to spot a bomb in someone’s boxer shorts they can also detect prostheses, the results of plastic surgery and evidence of transgender. But while the thought of having your body viewed and photographed in all its naked glory by a stranger just to go on holiday may make many people uncomfortable, the privacy argument largely misses the point.

Many people would agree, after all, that being scanned briefly by a machine – assuming the images are viewed remotely by an operator and then destroyed, as is likely to be required – is ultimately less intrusive, less an inconvenience and less an invasion of privacy than having to remove your coat, your shoes and be patted down physically by a security officer.

The real issue therefore is not so much what these machines and their operators may be able to see in addition to a bomb, but whether full-body scanners can spot explosives at all and whether going to the enormous expense of installing them in airports would really make flying any safer.

On this, experts remain divided, and, fortunately for European governments’ overstretched budgets, so too is the EU, at least for the time being. Though scanners have been installed experimentally at airports in London and Amsterdam – from where 23-year-old Abdulmutallab boarded his Detroit-bound plane – there are no plans as yet to make their use obligatory at European airports (though the British and Dutch now intend to install them permanently).

Scanner technology needs to be evaluated further with regard to privacy “guarantees and effectiveness,” Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the current term president of the EU, said in early January. He added that installing them is not a decision that can be taken “unilaterally.”

Spain has no scanners in operation, and as yet no plans to install them.

Until now, the EU has left it up to individual member states to decide whether to use body scanners at airport checkpoints. In 2008, the bloc suspended work on draft legislation regulating the use of body scanners after the European Parliament demanded a more in-depth study of their impact on health and privacy. However, in the wake of the attempted Christmas Day bombing, EU officials are busy re-evaluating security regulations, and inevitably will find themselves under pressure to make scanner use widespread.

The United States, which currently operates 40 scanners at various airports throughout the country, will almost certainly urge Europe to scan many – if not all – passengers on US-bound flights. And, just as the EU gave in to US demands on passenger information and biometric passports – albeit not without a fight – it will probably eventually give in on full-body scanners as well.

Spain’s public works minister, José Blanco, admitted as much after meeting with US officials in Washington in early January.

“The use of scanners in airports will be inevitable,” he said, adding, nonetheless, that an EU-wide agreement governing their use would need to be reached first.

Pressure is also likely to come from the general public – and demands for authorities to “do something” to keep travellers safer would certainly have been greater had Abdulmutallab brought down the Northwest Airlines plane.

A USA Today/Gallup poll, conducted January 5 and 6, found that 78 percent of US respondents favoured the use of scanners in airports, while a survey conducted by The Canadian Press Harris-Decima found that four in five Canadian respondents said the use of the scanners was reasonable. A poll by Angus Reid Public Opinion, showed that 78 percent of respondents in the United States, 73 percent of Britons and 67 percent of Canadians would prefer to be scanned rather than patted down by a security guard or police officer before boarding a plane.

A flight of blind faith?

Is this a case of blind faith on the part of both politicians and the public in an expensive and unproven technology?

Studies and anecdotal evidence certainly show that full-body scanning is no silver bullet when it comes to keeping airplanes safe.

Full-body scanners use either millimetre wave or backscatter technology. The first type sends radio waves over a person and produces a three-dimensional image by measuring the energy reflected back. The second kind uses low-level X-rays to create a two-dimensional image of the body. In an effort to assuage privacy concerns, current procedure – in both the United States and Europe – is for operators to view scans remotely and not store them. With regard to health concerns, proponents of body scanning note that the amount of radiation the machines emit during a typical scan is less than what a person receives by using a cellphone or spending two minutes inside an airplane.

While both types of scanners produce relatively detailed images, showing body features, breast implants or colostomy bags, they are generally unable to detect objects hidden in body cavities. And, more significantly, they may not be able to detect the kind of powder and chemical bomb components Abdulmutallab smuggled onto Northwest Airlines flight 253.

One British study found that millimetre-wave scanners could detect high-density material such as metal knives, guns and dense plastic such as C4 explosive, but not low-density material such as powder, liquid or thin plastic if the person being scanned was also wearing low-density clothing – the millimetre waves simply passed straight through.

German television station ZDF recently vividly highlighted the shortcomings of the machines in a demonstration that revealed that the device was able to detect little more than a cellphone, a knife, and the girth of the man walking through it even though he was also packing materials that could be used to make a bomb.

If full-body scanners might not be able to detect bomb-making materials of the kind carried by the 23-year-old Nigerian in his underpants, why the sudden focus on these machines as the next step in ever tighter airport security? And, though 100 percent security is never attainable, could the money that would be spent on deploying thousands of these machines at airports around the world – as will probably be the case – not be better spent elsewhere?

Each machine costs between 100,000 and 150,000 euros and dozens would be needed in a large international airport to handle the numbers of passengers and minimize inconvenience (scanning a single passenger with a millimeter-wave machine takes around 40 seconds). And, if not all passengers are scanned, then the effectiveness of the technology is ultimately reliant on how effectively high-risk passengers can be identified.

“It may turn out that we can reduce the overall risk of a successful terrorist attack far more by investing in additional intelligence analysts, or consular officers in high-risk countries, than purchasing expensive new screening devices,” notes David Schanzer, the head of a terrorism study centre at Duke University and the University of North Carolina.

That is certainly one option. The other, of course, is for Western governments to spend more money, time and effort on tackling the social, political and economic problems that lead young men like Abdulmutallab to want to blow up a plane in the first place. Or which lead fellow would-be terrorists to target trains, buses or city streets, where, incidentally, no one has to pass through a body scanner.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.